A Scientific Pantheist’s Meta-Ethical Alternative to Sam Harris’s Utilitarianism

A Scientific Pantheist’s Meta-Ethical Alternative to Sam Harris’s Utilitarianism

By Benjamin Yoke

After rising to prominence in the “New Atheists” movement, Sam Harris has become one of the more famous intellectuals in the last decade or so to promulgate an ethical system ostensibly based on science and reason. Like many secularists before him Harris tries (somewhat quixotically) to construct a scientific meta-ethic based on utilitarianism. In this essay I will argue that a scientific pantheist’s worldview delivers a more reasonable, instructive, workable/pragmatic, “scientific”, and profoundly more existentially relevant ethical paradigm.

Harris’s Argument for a Utilitarian Ethic (Synopsis)

Mr. Harris’s ethical system is more or less classic utilitarianism, where utilitarianism is defined as a system of ethics whose central goal is to promote the greatest happiness for the greatest number. Once one accepts his founding, or base, utilitarian premise that “we ought to maximize the well-being of conscious creatures”, he thinks it is then simply a matter of utilizing the scientific method to find out how to maximize such well-being.

Harris’s main arguments, for accepting his foundation for an ethical premise, are as follows:

Argument A. Caring about the well being of conscious beings is the foundation (or starting point) for a reasonable ethical system, because a universe without conscious beings would be a universe without anything that could value well-being and the avoidance of suffering.

Argument B. If we imagine the worst possible universe where all conscious creatures suffer as much as possible, then we have to think that is bad. If you claim you don’t think that’s bad, that maybe there is something worse, then Sam Harris claims he doesn’t know what you are talking about, and he says you don’t know what you are talking about either. Therefore, once we admit that the worst possible universe inherently needs to be avoided, then, according to Harris, we must buy into applying the scientific method to discover how best to move away from suffering to the maximization of well-being.

Argument C. Science can be applied to maximizing something as subjectively experienced as well-being. Because, Harris notes, in medicine the sensation of pain is generally accepted as a “subjective fact”, and thus the “fact” of well-being, as the central goal of conscious beings, can likewise be subjectively, but factually, extrapolated.

Argument D. Harris points out that, an ethical system truly based on science and reason would surely have a great advantage over previous religion based systems. Since virtually all of modern humanity accepts, or uses, and lives with modern technology, it is implicit the we must also except the utility of science that enabled us to create it.

Thus it is understandable and interesting that Harris has attempted to create an ethical system based on science and reason.

A Scientific Pantheist’s Meta-Ethic (Overview),

as an alternative to Harris’s meta-ethos.

Pantheism is simply the belief that nature and God are one and the same thing, or that the universe or nature as a whole is god. The utility of pantheism, particularly in this discussion, does not turn on metaphysical or ontological arguments for pantheism. Rather pantheism’s utility is meta-ethical. i.e. It is pragmatically desirable to consider the universe or reality as a whole as God, and that’s meta-ethically synonymous with viewing the universe as a whole as being the good.

Perhaps Einstein (the greatest scientist of our era) best expressed the way in which Scientific Pantheism can/should be the basis of a meta ethical system, when he said,

“A human being is a part of the whole, called by us “Universe.” He experiences himself, his thought and feelings as something separated from the rest – a kind of optical delusion of his consciousness. This delusion is a kind of prison for us, restricting us to our personal desires and to the affection for a few persons nearest us. Our task must be to free ourselves from this prison by widening our circle of compassion to embrace all living creatures and the whole of nature in its beauty.” (bold font mine)

“A human being is a part of the whole, called by us “Universe.” He experiences himself, his thought and feelings as something separated from the rest – a kind of optical delusion of his consciousness. This delusion is a kind of prison for us, restricting us to our personal desires and to the affection for a few persons nearest us. Our task must be to free ourselves from this prison by widening our circle of compassion to embrace all living creatures and the whole of nature in its beauty.” (bold font mine)

As the last portion of the Einstein quote makes clear, Scientific Pantheism’s meta-ethos isn’t just about a concern for the well-being of conscious creatures; it extends concern to unconscious life, and then to the entire universe. Extending compassion to reality as a whole causes Einstein’s prescription to transition, from not just an ethical sentiment, but also to a “transcendent” religious sentiment. But, though it is certainly more like a religion than utilitarianism, scientific pantheism affirms that the best way to know what in fact nature consists of (what the truth is) is through modern science. Unlike in monotheism or deism, the scientific pantheist typically posits that there is insufficient evidence to assume agency/sentience to the universe as a whole. Nor is there enough evidence of a particularly significant (or perhaps any) supernatural element to or “behind” God/nature. However, just as scientists rigorously study nature via the scientific method to approach the most pragmatic, and best, approximation of the truth, scientific pantheists pragmatically hold that acting in accord with such truth (as to what nature/god is) is the good.

It is important to make it clear that a reasonable pantheist believes that only in general (inductively) is nature (the universe) The Good, and thus worthy of the reverence and love one would accord to a god. This general love and reverence is analogous to the love one feels for one’s spouse or friends in that, even though they may have specific flaws (sometimes even awful flaws), in general you love them because, for you, they have more good attributes than negative ones.

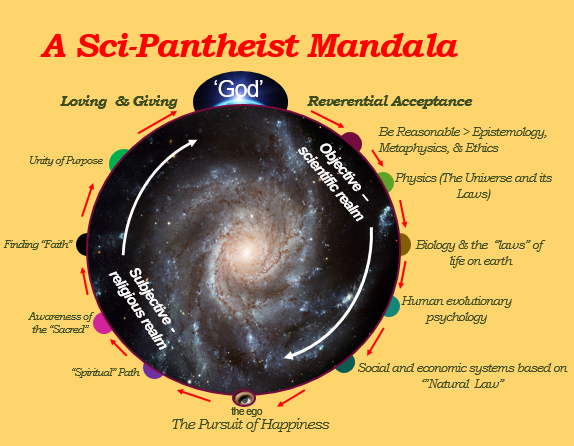

Moreover, scientific pantheism thus also offers an ethical hierarchy that tracks the hierarchy of the sciences, from loving the universe as a whole (in general/inductively), and thus choosing to act in accord with the universe’s “laws” as a whole, and then from those universal laws (of physics) deductively down through chemistry, and biology, and through human evolutionary psychology, to the self (see the right side of mandala below). This creates the most coherent and pragmatically useful world view meta-ethos; because it is by definition profoundly in accord with reality, as known by modern science. And, curiously, it also resolves naturalistic fallacy issues.

This resolution occurs because, once one understands the nature of the general to specific meta-ethical value hierarchy (where each value going down the right side of the depicted mandala is a subset of, and subservient to, the values above), where the top value is accepting the universe as a whole, and acting in accord with it’s most general relationships/rules (physics), we see that the fallacy only happens when we think we should act in a accord with a lower (less general) form of natural order that may itself be out of accord with a higher (more general form of natural order).

When we examine this hierarchy of natural order, which tracks the sciences, from the universe as a whole down to the self, two crucial values (that humanity has, as of yet, failed to sufficiently adhere to) become clarified:

A. We should act in accord with the definition/meaning/“laws” of life.

B. We should create and maintain a gracefully sustainable civilization.

Let’s expand on these two deduced values:

Let’s expand on these two deduced values:

A. We should act in accord with the definition or “Meaning” of life.

i.e. By pantheism, we should accept that an essential part of The Meaning of Life is the same as the definition of life, and is thus a law (normative prescription or purpose) of life…

So, again, if you look at the super-set to subset ethical hierarchy that a scientific pantheist would reverentially accept, on the right side of the Mandala, then we start by accepting that we should act in accord with the universal laws of physics. However, most people are practical enough to generally in principle accept the sane utility of acting in accord with the laws of physics (save for the occasional quixotic attempts at being something such as a breatharian or flying swami). But, when it comes to reverentially accepting what humans are, biologically (accepting the “laws of life on earth”), that means accepting that the Meaning of our lives should in significant part be the same as the physical definition of life, homo sapiens have normally chosen values (and thus actions) that skew slightly (but significantly!) from the reality of the process of life as understood by science. At this critical point in human history, rectifying this clear and deeply significant skewing of values at the middle of the natural value hierarchy should surely be the central task of the scientific pantheist. For what it’s worth, the survival of human civilization almost certainly hinges on it.

This should be common sense: not adhering to the definition of life means death and/or extinction. And yet the vast majority of humans bridle, nihilistic-ally and somewhat insanely (with our mal-evolved ego-centric consciousnesses), at the suggestion that the Meaning (or purpose) of one’s life should be such a “low” thing, as to be the same as acting in accord with the definition of life.

Allowing the definition to become our Meaning, is so important that it is probably the key that, if we do it, will allow humanity to make it through the great (hazardously powerful technological civilization) extinction filter, and thus beat Fermi’s paradox.

So, what is the physical definition of life that (in the sci-pantheist meta-ethic) humans should strive to be/act in accord with? Roughly it is this:

Life is: an individuated metabolic process (thermodynamic dissipative structure) that has become organized around the ability to creatively* sense and respond to it’s environment to avoid its own dissolution. (link)

*To avoid confusion, it should be pointed out that the concept of creativity, as it is used here, doesn’t necessarily require conscious intent. Creativity can be here defined as, any natural process (algorithm) where functional order is formed out of chaos, and at some point in that algorithm a random variable is interjected such that the resulting new order is relatively unique. Some examples: the root ball that any tree in a forest creates is unique, the particular exact path any bee creates to get pollen and nectar out of the flowers in a meadow is unique, and a new species created via natural selection is unique.

Since the definition of life above is derived via understanding life in terms of the universal laws of physics, it is very likely that this definition (or theory of life) would apply to anything we would call life in the universe. On earth the “metabolic process” has been going on (avoided dissolution) for four billion years, and we (along with every other living organism) are the leading end/edge of that profoundly ancient process, that thus far (as long as it is life) will continue to avoid it’s own dissolution. Pretty cool! As scientific pantheists, i.e. as lovers of this universe/reality, and the opportunity to exist in it, a central task as a part of life is to use all the skill that we possess to sense and respond to the environment we inhabit to creatively avoid the dissolution of the four billion year old metabolic process that moves through us, as far into the future as we can influence.

A typical response to the ethical maxim elucidated above is that it is sounds like another form of social Darwinism (broadly defined). It is not. Life is organized around the ability to avoid its own dissolution via sensing and responding to its environment. Evolution through natural selection is only a subset category of the way life can sense and respond to its environment. There are many examples of species in nature that are well adapted enough to their niches that they don’t appreciably evolve (i.e. don’t have to evolve) over time. Crinoids, turtles, cockroaches, species in the kingdom archaebacteria, etc., have been around relatively unchanged for millions or even billions of years. Sensing and responding as individual organisms, or collectively, is sometimes sufficient. In fact, as many dead Nazis “learned” by losing WW II, embracing social Darwinism (“natural” selection) as a core collective ethos often may reduce the odds of your particular portion of the metabolic process being passed on, through reproduction, into the future. Regarding the threats of climate change, nuclear war, AI, or overpopulation, we have a choice: do we sense and respond vitally to the threats to the metabolic process that moves through us? Or do we let natural selection by default run its course? Either way life is likely to continue (though possibly profoundly diminished), but by choosing the former option, we are individually choosing to be in accord with the physical definition/Meaning of life, and life will continue with us (and hopefully even enhanced by us), rather than without us.

B. The Importance of Human Civilization

Doing one’s best to cultivate a gracefully sustainable, peaceful, human civilization that ideally would last millions or even billions of years into the future, is a central value that arises logically from the scientific pantheist’s meta-ethical system.

Why? Because of the profound synergistic survival benefits human individuals accrue by playing positive sum games. For the first 3.5 billion years life existed on earth there was only single cell life. For the last half billion years, one sixth of life’s history, there has been multi-cellular life. That really changed things on our little planet. As per game theory, we can say that for the cells cooperating in an organism life is not a zero sum game. By cooperating, the cells gain more than they give. The sum of the whole together is greater than the sum of the cells separately. That’s synergy.

Due to the phenomenal ability of humans to take advantage of synergistic cooperation, virtually all seven and a half billion of us are now cooperating (more or less) in a worldwide civilization. Currently almost the entirety of homo sapiens is participating in a single worldwide economy. Not only that, but of course we also share language, writing, vast amounts of knowledge, specialized trades and skills, the physical and abstract artifacts of our fore-bearers, etc., etc.. Obviously no other life form in earth’s history has done this. And, if we get it right, and if it functions in accord with the larger biosphere (and the vastly larger reality of which it is but an infinitesimal part) it should be obvious that human culture generally and modern civilization specifically are phenomenal tools for survival, for us, and our genes, collectively, and individually. That is to say, civilization can be a synergistic niche that will work for us, as parts of an individuated thermodynamic structure, to maintain the metabolic process that moves through us into the distant future.

Perhaps the hallmark of civilized behavior, is how we behave in our interactions with any random stranger; normally it’s in a way that’s likely to cause a positive sum game synergistic benefit. It is from this subconscious cooperative understanding that the utilitarian’s maxim of optimizing the well-being of conscious creatures organically really arises. Thus, although well-being is a very important ethical value in a reasonable meta-ethical hierarchy, well-being should not be the highest value in the most reasonable “scientific” hierarchy (rather than being at 12 o’clock, it is at around 4:30 or 5 o’clock on the mandala).

So to conclude, why is scientific pantheism’s ethical paradigm better than Harris’s utilitarianism?

Something like 99.9% of the species in earth’s history have gone extinct. Undoubtedly, life for the organisms in those species continued as it “always” has, until it didn’t. In terms of the laws of physics and the complex nature of chemical reactions, any living system has to be doing a lot of things right just to be alive at all. But nature can be a stern task master, and the extinction rate informs us that it is often the case that an organism (or the members of an entire species) only need to miss the requirements of survival by a tiny margin, and the game is over. From a scientific pantheist’s perspective, utilitarianism’s prescriptions (including Harris’s utilitarianism) are generally correct or close to correct in articulating the “good”, but the meta ethos still misses the mark. And if utilitarianism were to be fully embraced by our species (even though utilitarianism may be a better ethical system then most that have preceded it), then it will still likely lead to our extinction. And, further, since an explicit or implicit utilitarian ethos has powered much of the values of modern civilization, and since human civilization is changing or “advancing” at an alarming exponential rate, such that human caused existential crises are stacking up (AI, climate change, nuclear war, overpopulation, etc.), such that extinction (or at least the premature death of billions) is likely coming sooner, rather than later. So, if Harris’s Utilitarian ethos can be summed up as “maximize the well-being of conscious creatures”, how shall we sum up the scientific pantheism ethos?

It can be summed up thus: Learn to love reality enough, such that we choose to act in accord with nature, in accord with what life is; to creatively avoid the dissolution of the metabolic process that moves through us, as far into the future that we can reasonably influence (the hopeful vision is that eventually this even means billions of years). And, pragmatically, this generally means play positive sum games in our interrelations with fellow humans and with nature as a whole.

If you wish to see the summation above explained a little more deeply, then feel free to examine the -

Problems with Harris’s Utilitarian Ethic & Scientific Pantheism’s Solutions:

(Scroll down, or simply click on the link, for the numbered comment below in order to go to the respective essay in which you have interest.)

1. In the natural world, “The well-being of conscious creatures” is logically and empirically subservient to survival, not vice-versa. (Link)

2. Utilitarianism is prevalent now, due to its being a historical artifact, rather than it simply being the most reasonable non-supernatural basis for a meta-ethos. (Link)

3. “Survival” may be mostly about niche maintenance, rather than natural selection. (Link)

4. For Harris, precisely when and why in biological history does consciousness disconnect, as an artifact of selection for survival, such that its “well-being” becomes hierarchically a superior moral value, above survival? (Link)

5. The crux of the biscuit: the core reason Harris’s utilitarianism, or any utilitarianism, isn’t up to snuff as a meta-ethos, is that ultimately it is too dis-functionally solipsistic and egotistical. (Link)

6. Harris’s incoherent jump: from valuing scientific objective truth, to valuing “the well-being of conscious beings”. (Link)

7. Harris’s Utilitarianism can’t utilize Unity, with a capital U, from monotheistic religion (where God is the unifying concept) or modern materialistic science (with it’s universal laws of physics). (Link)

Which leads us, curiously, to:

8. Is/Ought “Resolved” (Link)

9. Harris’s bootstrapping of the utilitarian value of well-being is a linear un-modern-scientific Aristotelian deductive process. (Link)

10. The scientific pantheist’s position on the well-being and prevention of suffering of non-human conscious creatures: (Link)

11. Isn’t biological survival an inherently selfish concept, and won’t a mandate to reproduce exacerbate overpopulation? (Link)

12. Aren’t Utilitarians concerned about existential threats anyway? (Link)

13. AI (Artificial Intelligence) and Scientific Pantheism (Link)

14. Harris’s ethos is an exacerbation, instead of alleviation, of the separation of consciousness from reality that Einstein (and religious sages) spoke of. (Link)

15. But do humans naturally care about reality as a whole more than the well-being of conscious creatures? And if that is what we should, regardless, do how do we make it happen? (Link)

16. God – Pantheism, Theism, and Atheism (Link)

17. Faith (Link)

18. What is Life? (link)

19. On the Self and Selfishness (Link)

>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>

Conclusion

A meta-ethos based on scientific pantheism would be more coherent, more in accord with the hierarchy of the hard sciences, more in accord with the epistemological methods of science, more unified, more spiritually nourishing, less solipsistic, and much more likely to lead to a sustainable human civilization, than Harris’s utilitarianism.

1. “The well-being of conscious creatures” is logically and empirically subservient to survival.

1. “The well-being of conscious creatures” is logically and empirically subservient to survival.

Biologically, “the well-being of conscious creatures” is logically and empirically subservient to survival, not vice-versa.

i.e. We empirically observe, and can logically conclude, that evolution created the desire for us to pursue “well-being” (which we then use as as a meaningful concept) because conscious creatures experiencing subjective well-being from breathing freely, a full belly, sexual satisfaction, loving offspring, etc., are likely to survive. But the reverse is not the case: empirically well-being is a subset, non-essential, aspect of survival. Because, for one thing, obviously survival of life forms predated, and can occur without, conscious life forms who could even experience subjective well being.

So, by placing well-being at the top of their moral hierarchy Sam Harris and the utilitarian’s have created a normative system that will often be out of accord with what scientifically is the case. Obviously, it makes no sense to say that we just happen to pursue well-being randomly, just tautologically because that’s what conscious creatures like.

For the utilitarian, long term survival of the metabolic process that moves through us, via reproduction into the distant future (the essential “survival” part of the literal meaning/definition of life), would only be of interest if it leads to well-being, not vice-versa. Utilitarians found (base) their value systems in the subjective conscious experience of well-being; not in the physical world as a whole (then the biological world as a subcategory of that, then conscious beings as a subcategory of that). Thus, when the hard science of biology (and thus biological survival) is suggested or implied as a precursor value base, they tend to respond with a straw man argument against biological evolution as a base. The closest Harris comes to addressing this issue is to say that a scientific account of human values “is not the same as an evolutionary account.” For example, in the introduction to The Moral Landscape, Harris admiringly quotes Stephen Pinker’s (another utilitarian) stunningly unscientific, ignorant, and dismissive straw man argument against attempting to make a biological survival based ethical foundation:

“If conforming to the dictates of evolution were the foundation of subjective well-being, most men would discover no higher calling in life than to make daily contributions to their local sperm bank.”*

Well, though evolution has dictated that such a survival strategy kind of makes sense for certain kinds of male fish, or the male portions of pine trees (spreading sperm and pollen far and wide), it doesn’t for homo sapiens. Evolution has “dictated” that members of homo sapiens employ far more behaviorally sophisticated reproductive strategies than pine trees. And, even with fish and pine trees, evolution has dictated that most of the business of living (being an individuated thermodynamic dissipative structure) is more about respiration and finding food for the individual fish, and respiration and finding sunlight, water, and minerals for the individual tree. Perhaps Harris and Pinker’s simplistic idea of the “dictates of evolution” would apply best to a simple virus. However, virus’s have no metabolic apparatus. They aren’t cells. Their “purpose” is only all about spreading genetic copies of themselves. And so, crucially according to most biologist’s viruses can only marginally be considered lifeforms.

With Harris and Pinker’s straw man “dictates of evolution” argument, one is reminded of the comic absurdity in the 1980 Saturday Night Live sketch, were Rodney Dangerfield is worn out because so many women are clamoring for his sperm at the local sperm bank.  With homo sapiens a cast your genes far and wide strategy, would, at best, only work for a very few lucky individuals. In reality, the dictates of evolution cause most men to note that, in uncontrolled “free market” sperm banks, virtually all women go for the handsome 6’3” star quarterback Harvard graduate. Most men don’t qualify. And because most men don’t qualify, most men wouldn’t have much reason to peacefully participate in such a society. Most men can easily figure this out.

With homo sapiens a cast your genes far and wide strategy, would, at best, only work for a very few lucky individuals. In reality, the dictates of evolution cause most men to note that, in uncontrolled “free market” sperm banks, virtually all women go for the handsome 6’3” star quarterback Harvard graduate. Most men don’t qualify. And because most men don’t qualify, most men wouldn’t have much reason to peacefully participate in such a society. Most men can easily figure this out.

In a scientific pantheist society the awareness of the most rational ethos would presumably be more subtle. Thus, regarding the sperm bank example, in a functional sustainable positive sum game civilization (a “biological niche” which enlightened human organisms should rationally choose to participate in for the synergistic survival benefits) an individual donor’s sperm would generally probably only be allowed for the creation of two offspring at most. Because current sperm banks, where one male can create thousand of children Darwinian evolution has free reign. And such unfettered Darwinian evolution is ultimately antithetical to a sustainable civilization/niche.

Seen in this light, conforming to the dictates of survival (rather than evolution) is, or should be, the ethical foundation that precedes subjective well-being, because with the scientific pantheist meta ethos a sophisticated benevolent morality can be established the is in deep accord with what we as homo sapiens psychologically and biologically are, according to science.

To explicitly clarify what is going on here, please consider the utilitarian versus pantheistic moral systems being advocated in terms of two distinct concepts: evolution and survival. When the utilitarian is asked to consider basing an ethos on hard science based biological survival, in this contemporary cultural milieu they have been reflexively and incorrectly presuming that means an ethos advocating biological evolution. Evolution is not even an essential part of the definition of life; as can be logically demonstrated by a theory/definition of life based on the universal laws of physics (given in the main essay above, and further elucidated in a sub essay below), and empirically demonstrated by life forms that have survived, but that haven’t evolved appreciably since the dawn of earth based life. Considering the near certain zero sum game nature of survival via biological evolution, versus the possible positive sum game nature of survival via human civilization, biological survival for the metabolic process that moves through individual modern homo sapiens (or for homo sapiens collectively as a species) is not best facilitated by an ethos that generally sees biological evolution as a positive.

So, since the natural order is, well being is important because it leads to survival (not survival is important because it leads to well being), the natural order is more scientific and more in accord with reality. And, the common utilitarian argument against put survival first is simply the straw man that “survival” necessitates some sort of social Darwinist ethics.

Then what, once again, is the resulting central pragmatic difference for humanity, between the likely utilitarian ethos of Harris, and the likely Scientific Pantheist ethos? Simply put, biological survival is much more of a big picture, long term, even eternal goal. Whereas well being tends to be more of a short term, or even immediate goal. In its worst manifestation, well being as a goal leads to simple hedonism. After all, the heroin addict experiences great well being, temporarily; as does this fossil fuel addicted society. The more enlightened and more common utilitarianism of Peter Singer or Bill Gates quite laudably can and has alleviated a great deal of suffering, but their efforts spent on the short term alleviation of suffering has been at the expense of effort that could have been spent on securing the long term survival of our civilization, on which the survival of the metabolic process of life that moves through us depends. So, from the scientific pantheist perspective is this an either/or situation? Is a sci-pan meta ethos all about survival at the expense of well being? No. Psychologically well being is necessary for oneself because it motivates one to work for survival. And altruistic and empathetic acts directed towards the improving the well being of others is necessary, because it strengthens the fabric of civilization (it’s civilized!) And civilization, done right can, be a phenomenally benevolent biological niche for not just the survival of individual homo sapiens, but of life on earth.

*Sam Harris, The Moral Landscape T (New York: Free Press, 2010), 13

2. Utilitarianism is prevalent now, due to its being a historical artifact,

2. Utilitarianism is prevalent now, due to its being a historical artifact,

Utilitarianism is prevalent now, due to its being a modern historical artifact, rather than it simply being the most reasonable non-supernatural basis for a meta-ethos.

To put our civilization’s current ethical philosophical situation in context, please consider how attempts such as Harris’s to derive an ethical system via objective science falls in line with the enlightenment agenda. Then consider how “enlightened” thinking has evolved in the last couple hundred years:

- Champions of the enlightenment believe that by using reason, and a scientific understanding of the natural world, we can make the lot of humanity better.

- Traditional enlightenment philosophers believed that by studying the natural world, we could derive “natural law” fundamental values from which to build our social contract.

- Thus, as science progressed so did, or should, natural law enlightenment values. And, after Darwin, the older natural law values, such as “Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of Happiness”, were no longer understood or valued in their older teleological way as naturally derived rules for coming into accord with “God’s will” over nature, so much (post Darwin) as examples of archetypal values of the human psyche, that simply arose out of natural selection. From an evolutionary perspective, the consciousness’s desire for “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness”, is merely a manifestation of natural selection that leads to survival. So, survival really took hold in the West’s zeitgeist as the top value of the enlightenment hierarchy. And survival of the “fittest”, after Darwin, was an assumed corollary value, that was then all too often mistakenly followed. This social “Darwinism” wasn’t always the explicitly worked out moral system of Herbert Spencer. Although it often was. Spencer is generally maligned today, during his lifetime he enjoyed unparalleled respect as a philosopher. Rather social Darwinism was/is an implicit fairly amorphous value that stood/stands behind a lot of disastrous 19th and 20th century moral philosophy, and the resulting zero sum game political and economic experiments:

Eugenics was paired with “meritocratic” capitalism,

Eugenics was paired with “meritocratic” capitalism,

Marxist systems where “reactionaries” were “rightfully” weeded out (murdered) in the dialectical inevitable “progress” of history towards socialist utopia,

Fascist experiments where “superior” races worked to subjugate or exterminate “inferior” races.

- That obviously led to some profound negative consequences. And, by the 1960s after two disastrous world wars, the holocaust, the dawning awareness of the evil dysfunctional irrationality of racism and sexism, and the insane threat of global nuclear war (all started by the “enlightened” West), there was an understandable global questioning of what were felt to be the implicit (at least) core values of “enlightened” Western civilization. So, it was in the 60’s that the world saw a counter enlightenment resurgence, of supernatural religious dogmatism among those disposed to a conservative mindset, and a new age grab-bag of super-naturalism and hedonistic sensual-ism from those of a liberal mindset. There was (and is) also a vacuous hedonistic default valuing of rampant consumerism that arose from both sides. The affects of the conservative and liberal counter enlightenment are still being felt today.So pursuing happiness (or well-being), because of the deeper value, that it is a biologically evolved mechanism that tends to lead to survival, has fallen out of fashion. Because in the zeitgeist “survival” is irrationally and unscientifically associated with the zero sum game biological evolutionary “survival-of-the-fittest” “scientific” social experiments of the 19th and 20th centuries. And so secular folk have assumed they been left with utilitarianism, kind of by default, even though it isn’t really in natural harmony with hard science.

And social Darwinism (which remains antithetical to civilization) still haunts us. Curiously, in it’s most explicit form it is found most often in some segments of the “environmental” movement. Where the various existential crises that humanity has recently created are met with the resigned or even gleeful belief that it is “natural”, and thus good, that nature will wipe us out.  The idea being that we are destructive vermin, not fit to survive.

The idea being that we are destructive vermin, not fit to survive.

But, of course, what is truly natural and environmental for us, as life forms, is for us to work with all of our being, to creatively avoid the destruction of our biological niche, to benevolently fit in, not to nihilistic-ally resign ourselves to destroying our niche and thus ourselves.

3. “Survival” may be mostly about niche maintenance, not natural selection.

3. “Survival” may be mostly about niche maintenance, not natural selection.

Another way to explain the survival, versus survival of the fittest, misunderstanding, is in terms of the biological concept of niches. If an individual or species is well adapted to their niche, then significant biological evolution is unlikely to occur. From the individual’s, and the species, perspective this is a good thing. It means success. It means the scythe of natural selection is far less likely to weed you and most of your reproductive cohorts out of the gene pool. From the definition of life, it means that you have the ability to avoid the dissolution of the metabolic process that moves through you, via your genetic descendants, into the future.

To understand niches in another way, consider that within yourself and your cells there is homeostasis. That is to say, your internal chemistry is organized such that there are physical conditions that can maintain the thermodynamic dissipation, or metabolic process, that moves through you. Homeostasis is the equivalent of you (or your cells) doing what’s necessary to keep one of the most obvious of non living dissipative structures, a campfire, “alive” (one must provide fresh air, the right temperature, fuel, avoid letting too much rain hit the fire, etc). But that homeostasis is within cells and organisms. . . and, a niche is where an organism or species can maintain external homeostasis.

Organism’s may also continuously alter and/or maintain their niches into “homeostasis”. They typically need to exert substantial control over their external environments that, if ignored, may also put out the metabolic process:

Trees grow towards the sun. Animals go where the food is. Many fish species swim in schools to minimize the chances of being eaten. Mammals create wombs for their youngest offspring, milk for their slightly older offspring, and train and nurture their growing young. Bees, termites, ants, and beavers alter/maintain their niches profoundly with hives, dams and lodges, etc.. Humans are perhaps the first species to have now created a globe spanning niche. It’s called modern civilization.

Trees grow towards the sun. Animals go where the food is. Many fish species swim in schools to minimize the chances of being eaten. Mammals create wombs for their youngest offspring, milk for their slightly older offspring, and train and nurture their growing young. Bees, termites, ants, and beavers alter/maintain their niches profoundly with hives, dams and lodges, etc.. Humans are perhaps the first species to have now created a globe spanning niche. It’s called modern civilization.

Human civilization is obviously potentially powerful and resilient (though, thus far, in many ways it’s also precarious and self destructive). Still, surely it has the potential to be the most beneficial niche of all time for life as a whole in this solar system. For example, with civilization, the metabolic process that moves though us and our fellow species could avoid dissolution, even when the sun has entered its red giant phase which will encompass our mother earth. With our civilization we, and such millions of other earth species as we choose, could move off planet and out into the solar system, and hopefully perhaps even to other star systems. Successful life (for almost all individuals and species) is almost always more about surviving by being well adapted to, and maintaining, a niche, then it is about “surviving” “red in tooth and claw” via competition and natural selection. Why? Simply because most individual’s and specie’s metabolic processes live on via the former, but die out via the latter.

Post Darwin, and to an extent even post Hobbes (with his belief that nature is “red in tooth and claw”), survival has generally mistakenly been taken to mean survival of the fittest. Now however, humans will hopefully act in accord with a scientifically correct definition/Meaning of life. And we will learn simply that the survival of the metabolic process that moves through us (hopefully into the distant future) is most likely assured collectively and individually if we choose to play civilized positive sum games with one another – rather than uncivilized zero sum (conscious or by default) natural selection games.

4. For Sam Harris when does “well-being” become a hierarchically superior moral value, above survival?

4. For Sam Harris when does “well-being” become a hierarchically superior moral value, above survival?

For Sam Harris, precisely when and why in biological history does consciousness disconnect, as an artifact of selection for survival, such that its “well-being” becomes hierarchically a superior moral value, above survival?

Utilitarianism (including Harris’s brand) is out of sync with the natural order, and thus a confusion of values ensues with pursuing well-being generally more than survival, and specifically when determining which “conscious beings” have intrinsic value over the rest of reality:

- As a general value, since we all have only a finite amount of personal energy to employ in this life, a utilitarian is bound to focus on how he or she can most easily and effectively improve well-being. Peter Singer’s moral prescriptions are great examples of this. According to Singer two of the main areas one should focus on are preventable childhood disease and the factory farmed wholesale suffering of agricultural animals. That’s the low hanging utilitarian fruit, whereby vast amounts of suffering can be quickly prevented, and well-being thus enhanced. A scientific pantheist on the other hand will see these admittedly fine causes as, none the less, secondary. To the scientific pantheist well-being is still good, and suffering is still bad. But, they are secondary to survival and to alleviating the civilization wide existential/survival threats of: climate change, nuclear war, pandemics, threats to biodiversity, AI, asteroids, super volcanoes, etc. Survival comes first, and we should work to build a civilization where creating and maintaining all of the conditions for the graceful survival of the civilization is a top priority, and where new technological ideas must be rigorously screened and regulated, or encouraged, based on if they are a threat or a boon to the sustainability of the civilization.

To be clear and explicit: the enlightened perspective (when viewing the Mandala above as a whole) is that survival precedes happiness and well-being as a value. A scientific pantheist says this reality is inherently good (even sacred) enough that it is thus fundamentally better to suffer and not have complete well-being, then it is to be dead/extinct, and thus out of accord with life’s definition (and natural law mandate). Moreover, the scientific pantheist is far more likely to notice that, as increasingly secular humanity has cloven to the utilitarian creed, human well-being (at least) has recently somewhat increased (read Stephen Pinker’s Enlightenment Now), but so definitely have the number and degree of homo sapiens self created existential threats. This isn’t an accident or coincidence. It’s due to the skewed core values. Never before in recorded history has humanity, and a vast percentage of our fellow earthly species, faced existential threats of our own making. Now millions of species, the vast majority of humanity’s descendants, and human civilization, faces a vastly increased threat of premature death from climate change, nuclear war, population pressure, A.I., etc.. Welcome to the Anthropocene era; an era where human values are out of sync with the biological world.

-Specifically speaking, not only is subjective well-being hard to define (beyond simple physical pleasure and pain), but so also is the dividing line between conscious, or sentient, creatures (whose well-being alone we are to value) and the rest of life and the rest of the universe. It would seem that to the utilitarian a sequoia tree, a quartz crystal, a waterfall, or the planet Saturn, since they aren’t conscious or sentient, have indirect value at best, and no intrinsic value at all. But having a central nervous system, and thus the ability to suffer or experience pleasure, would make a gnat, a mouse, or a pig, intrinsically valuable. Beyond such a self/ego/consciousness referential conceit, and beyond the bizarre question of if a gnat can really ”value” it’s ephemeral well-being more than a venerable sequoia can. One has to wonder about the wisdom of constructing a meta-ethos where such peculiar boundaries between what is of intrinsic worth, and what isn’t, exist. Isn’t Einstein’s task (quoted above) more coherent?

5. Utilitarianism is ultimately too dis-functionally solipsistic and egotistical.

5. Utilitarianism is ultimately too dis-functionally solipsistic and egotistical.

The crux of the biscuit: the core reason Sam Harris’s utilitarianism, or any utilitarianism, isn’t up to snuff as a meta-ethos, is that it is ultimately dis-functionally solipsistic, egotistical, and self-interest based.

Beyond the moral criticism most of us direct against selfishness, on a practical or pragmatic level selfishness just doesn’t work. Beyond a certain point, selfish people generally don’t thrive. Once again, when we interact with one another in human society, we do it ultimately mostly due to the nature of the synergistic, positive sum game, benefits of collective behavior. This motive for behaving collectively, and thus valuing the collective, is what is actually at the root of the utilitarian ethos, but the problem is that the utilitarian perspective it still too limited.

So, rather than stopping at valuing the well-being of one’s self, one’s family, one’s tribe, humanity one’s species), or even Harris’s conscious creatures, the pantheist pragmatically takes this process to its logical conclusion: the scientific pantheist values the well-being of the entire universe. The pantheist understands Einstein’s extension of compassion, beyond conscious creatures to the entire universe (as quoted above). And it’s very instructive that, regarding Einstein, this led to an important, if pleasantly ironic, consequence: it was precisely by valuing the material universe (beyond and regardless of the well-being of conscious beings) that Einstein loved and cared about it enough that he was able to understand it enough that he could make his greatest contributions to the well-being of humanity.

The utilitarian may object, saying that one cannot play a positive sum game with non sentient objects and phenomena, that non sentient objects or phenomena, by definition, don’t care or benefit from our “compassion”. Perhaps. But, the ego at the heart of our sentience is rather ephemeral and insubstantial in the grand scheme of things as well. And the consciousness, as anyone who has successfully meditated might tell you, is most at peace when the ego is dissolved in the oneness of reality.

Perhaps the point here would be a little less esoteric if we bring it down to personal relationships. For example, we are supposed to love our spouses, friends, and family, and (even though there is always a selfish reason for loving one’s spouse) loving one’s spouse doesn’t really work if one is focusing on what one is getting out of it (more than one is focused on loving one’s spouse). That’s the crux of the biscuit: it’s that lack of self (conscious being) referential focus; that is the difference between scientific pantheism and utilitarianism. And by the way, it is also the difference between truly (benevolent) religious behavior and false religious behavior. . .

A quartz crystal. The elegantly beautiful universal relationships that special and general relativity describe. The ethereal, lifeless, vast, cold, storm and ring clad, beauty of the planet Saturn, etc., To perhaps most of us these have value, in and of themselves. We feel that it would be a good thing that these phenomena exist, even if we don’t. Even if no conscious being exists. Is this such a bizarre idea? Virtually all of us can imagine caring about the continued existence of our children after we die. And many of us like the idea of a tree growing and fed by our decaying bodies when we die (even if that tree isn’t sentient enough to consciously care about well-being). And there are certainly non living waterfalls I have known that I would like to think could exist here and on other planets throughout the universe, even if life itself didn’t exist. Why must everything refer back to the importance of consciousness, which only knows itself to be conscious via the ego? This self referential need is the heart of Einstein’s frustrating “optical delusion”.

And yet,

Harris and the utilitarian’s aren’t altogether wrong. They are close to correct. Their earnest concern for our civilization, and their stated commitment to science and reason, are why they are kindred “spirits” to pantheists. But, again, this quote from Harris shows he sees the logical root of value differently than Einstein:

“I think we can know, through reason alone, that consciousness is the only intelligible domain of value. What is the alternative? I invite you to try to think of a source of value that has absolutely nothing to do with the (actual or potential) experience of conscious beings. Take a moment to think about what this would entail: whatever this alternative is, it cannot affect the experience of any living creature (in this life or any other). Put this thing in a box, and what you have in that box is-it would seem, by definition-the least interesting thing in the universe.

So how much time should we spend worrying about such a transcendent source of value? I think the time I spent typing this sentence is already too much. All other notions of value will bear some relationship to the actual or potential experience of conscious beings. So my claim that consciousnesses is the basis of human values and morality in not an arbitrary staring point.”*

The key logical objection to this argument can be centered around the word “absolutely” in Harris’s third sentence. Everything in this universe is connected to everything else via space and time. So of course, since consciousness is required to value, in some sense everything is of value to conscious creatures. But that is an argument for pantheism more than utilitarianism; if one can value everything, then why is it, again, that we should value the well-being of conscious creatures in particular, such that it is the foundational value?

Harris then follows his comment above with the statement that “the concept of well-being captures all that we can intelligibly value.”** Followed by the argument that concern for the well-being of conscious creatures is inescapable, and as proof he lists examples of the self-interested nature of religious moral systems:

“The inescapable fact is that religious people are as eager to find happiness and avoid misery as anyone else: many of them just happen to believe that the most important changes in conscious experience happen after death (i.e. in heaven or in hell).”***

Then,

“The Hebrew Bible makes it absolutely clear that Jews should follow Yahweh’s law out of concern for the negative consequences of not following it.”****

Etc.

Yes, perhaps the hallmark of conscious creatures is our egos, and to remain conscious in this existence, at some point value structures return to our-selves. But religion, true religion (of which scientific pantheism is one), is about recognizing that at some point in the valuing one must (as Einstein said) extend the circle of compassion out beyond oneself, beyond all selves, to the transcendent God/universe. Ironically, Harris has acknowledged this via his “spiritual” discoveries of the release one (ha!) feels when, in meditation, the sense of self disappears. The biblical Jesus said, “There is really only one commandment: Love God with all your heart mind, and soul, and your neighbor as yourself.” Loving your neighbor as yourself may be utilitarian, but loving God with all your heart, mind, and soul isn’t. It is close to pure selflessness, like Harris’s spiritual experiences, like Einstein’s prescription. It’s true there is a sort of Zen paradox here, that: due, specifically, to the myriad, non-linear synergetic benefits of acting in accord with, not just the well-being of conscious creatures, but with this physical reality as a whole, the well being of conscious creature is actually more likely, if, ultimately one isn’t concerned about the well-being of conscious creatures, but with reality as a whole. It comes back to that old “optical delusion of the consciousness” thing that Einstein spoke of. And, it is also why there is a huge blind spot, in most secular utilitarians, that prevents them from understanding a certain pragmatic value to the core religious mandate: Jesus was right about the one commandment. And indeed, both the atheistic secular utilitarians, and the anthropocentric god defining, ego driven salvation wishing, theists, have generally missed the point of Jesus’s one commandment, Einstein’s quote, and the typical zen koan: we benefit most when in our hearts we really aren’t ultimately focused on our own benefits.

And one last point: Ayn Rand was perhaps contemporary humanity’s most ardent exponent for an ethos based on pure self interest. And yet even she was sane enough that when she really had to articulate “man’s noblest activity“, she said it was “productive achievement”. Why? What is productive achievement? Isn’t productive achievement creative production, where the productive achiever interacts, usefully, with the objective reality that is external to the self? And isn’t creative production the opposite of destructive consumption? And isn’t creative production thus a giving of the self to the larger/external reality, and destructive consuming a taking for the self? In Rand’s fiction she had her heroes claim what they were doing was for self interest, but the only reason her followers (to the degree that they were/are sane) were able to legitimately buy her definition of selfishness was that her heroes were “Fountainheads” who ironically thus gave so much.

*Sam Harris, The Moral Landscape T (New York: Free Press, 2010), 32

**Ibid., 32

***Ibid., 33

****Ibid., 33

6. Harris’s incoherent jump: from valuing scientific objective truth, to valuing “The well-being of conscious beings”.

6. Harris’s incoherent jump: from valuing scientific objective truth, to valuing “The well-being of conscious beings”.

Sam Harris makes an incoherent jump in values: from valuing scientific objective truth, to valuing “the well-being of conscious beings”.

Experience has taught us humans that a unified/coherent picture of the world, if such a picture is correct, is more useful than an incoherent picture. Incoherent disjointed scientific, religious, metaphysical, epistemological, logical, or value systems don’t work or function as well. By definition they are prone to chaos and paradox. That is why historians claim that Western philosophy’s first true philosopher was the ancient Greek, Thales, because he purportedly argued that everything is made of one unifying element: water. Thales was almost certainly wrong, but that’s not the point.

Finding a coherent/unifying model to explain astronomical observations is why Copernicus was driven to the hypothesis that the earth revolves around the sun. Coherence is why Newton’s uni-versal theory of gravity was considered so momentous. And it is why modern physicists are so obsessed with finding a theory that can unify general relativity and quantum physics. Coherent or unified models or theories are a hallmark of good science. It is why the most successful creators of grand unifying theories in science, such as Newton, Darwin, and Einstein, are considered to be the greatest scientists. So, a new theory or empirical observation that is not in coherence, with the unifying theories of physics that we have, would be highly suspect.

Likewise, the human need for a coherent social contract is also why the first of the 10 Commandments is to believe in one god. It probably wasn’t, as atheists often claim, because the Judaeo-christian God was simply a sociopath or megalomaniac. And coherence and unity is why the emperor Constantine saw fit to decree that Christianity be the one religion of the Roman empire. To the degree that these efforts at unity reflect the truth, we can easily see their merit.

Harris is a passionate advocate for atheism. And his central argument for atheism can probably be summed up as: religion, or more precisely supernatural monotheism, is out of accord (doesn’t cohere) with what science tells us is likely factually the case. Harris values science because it’s the best tool we have developed to learn what is the case. He believes that we ought to value what is. But he makes a categorically incoherent jump from valuing what is, in terms of the coherent body of knowledge that the hard sciences have given us, of which the universal laws of physics are underlying framework, to valuing the well-being of conscious creatures, which Harris arrives at separately. Harris doesn’t arrive at well-being via valuing the body of knowledge that is science, rather he attempts to bootstrap valuing well-being as his meta-ethical foundation, from his argument that we axiomatically must at least not want his hypothetical reality of ultimate suffering.

Scientific pantheists on the other hand, value science simply because science seems to shows us best what the truth is about reality (what reality is), and to the pantheist reality as a whole is the good. As a coherent whole, or, in general, reality/god is the unified value. The resulting coherent ethical system, of scientific pantheism, is thus less likely to have it’s “utilitarian” Peter Singers. Who, though well meaning and even heroic with their “effective” altruism, still spend too large a proportion of their precious energy alleviating suffering, while too little energy thus goes to avoiding or alleviating mounting existential threats.

Scientific pantheists on the other hand, value science simply because science seems to shows us best what the truth is about reality (what reality is), and to the pantheist reality as a whole is the good. As a coherent whole, or, in general, reality/god is the unified value. The resulting coherent ethical system, of scientific pantheism, is thus less likely to have it’s “utilitarian” Peter Singers. Who, though well meaning and even heroic with their “effective” altruism, still spend too large a proportion of their precious energy alleviating suffering, while too little energy thus goes to avoiding or alleviating mounting existential threats.

7. Harris’s Utilitarianism can’t utilize Unity, with a capital U.

7. Harris’s Utilitarianism can’t utilize Unity, with a capital U.

Sam Harris’s Utilitarianism can’t utilize Unity, with a capital U, from monotheistic religion (where God is the unifying concept) or modern materialistic science (with it’s universal laws of physics).

At best, Harris’s ethos leaves us with a (well-being of consciousnesses / respect for materialistic truth) duality, rather than a unity. It’s a contradiction laden meta-ethical consciousness/materialism duality, which, instructively, is similar to Descartes’s metaphysical mind/body duality. And indeed, the metaphysics of Descartes appears to resonate with Harris. In pod castes he has spoken of the primacy of consciousness as the first or fundamental thing we know, in ways that sound identical to Descartes’ “Cognito ergo sum.” (I think therefore I am). Harris’s spiritual experiences with meditation and psychedelics, and his predilections that led him to be a neuro-scientist, seem to have confirmed this for him. However, in response to Harris, and Descartes, a materialist might point out that, if one truly rigorously attempts to fulfill Descartes’ quest to doubt everything in order to find a point of certainty from which to found one’s philosophy, one finds that one can not but doubt the ability of one’s, or any, consciousness to exist, out of context with any larger reality. And therefore, when attempting to bootstrap a metaphysics or epistemology from Cognito ergo sum, one must admit that “I”, “think”, “therefore”, and “am”, are all hopelessly already too pre-understood/defined for one to say one has honestly doubted all but one’s consciousness. A thought experiment example of the difficulty of consciousness as half of a primary (duality) is: can anyone even imagine the existence of a consciousness in a perfect sense deprivation tank; a consciousness that could exist that had never not been in that tank? What could that consciousness possibly be conscious of? Consciousness could not value, period, without reality. Material reality comes first. But, contrariwise, it is easily possible to imagine a reality that could exist with no consciousness. Science tells us that was the case, there was no consciousness for most of the history on this earth, before brains evolved, and it’s what most of the universe is. In our one vast solar system, for example, it seems perfectly possible, very probable even, that only on the tiny earth does consciousness reside, and only relatively recently, and if the earth were wiped out we would no longer be around to know about it. We can easily imagine the solar system sailing unconsciously on.

The point here is that, just as consciousness is a manifestation that evolved out of the material reality of the universe, so in a consistent and pragmatic meta-ethos the well-being of conscious creatures arises as a sub-value of valuing the universe. And thus of valuing being in accord with physics and physically defined life in that material universe, first. Harris’s argument (A) from the synopsis of his position above can now be responded to with this: Caring about consciousness is NOT foundational, and attempting to make it so creates an unnecessarily dis-unified duality. Unnecessary because, a universe without conscious beings would be a universe without anything that could value well-being and the avoidance of suffering, but, according to our coherent and unified scientific understanding of the history of this earth in particular, and of the universe in general, it would at least still exist; unlike consciousness without a reality, as a sub-straight/foundation.

8. Is/Ought “Resolved”

8. Is/Ought “Resolved”

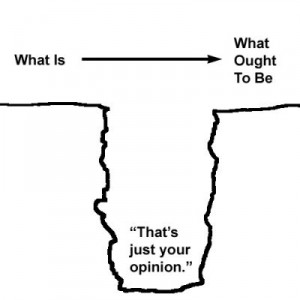

Is/ought is, arguably, the fundamental conundrum of philosophy. It is certainly one of the topics Sam Harris and his detractors struggle with, and that Harris has been accused of not adequately addressing. His ethical system’s incoherence (addressed above) is a good segue into the is/ought topic. But before we tackle it, let’s note that the is/ought conundrum is related to two other topics:

1. The naturalistic fallacy, which causes no end of confusion in human affairs; from irritation with enlightenment “natural law” prescriptions, to irritation with what the pop cultural value of “natural medicine” or “natural food” is. The naturalistic fallacy is related to the is/ought conundrum because just by saying that something is naturally the case, does not mean that it ought to be considered a good thing.

2. The argument from the existence of evil, which is used against theism by atheists, and which a consistent atheist would likely seek to levy against pantheism. Simply put, the argument from the existence of evil is: If God is all powerful and all good, therefore evil could not exist. But evil does exist, therefore an all powerful and all good God does not exist.

The argument from the existence of evil’s connection to the is/ought conundrum is a bit more obscure, but its connection is particularly relevant to the pantheist:

If, (a) what ought to be is the good, and if (b) according to a pantheist nature (what is) is the good, to the degree that it is god, therefore (c) nature is what ought to be. But, then how do we account for evil? How do we account for childhood cancer, or earthquakes, or murderous sociopaths?

So then:

What is the scientific pantheist’s position on is/ought? How should we get from our knowledge of what is to deciding what ought to be? And if pantheism can satisfactorily resolve is/ought, does that also help us avoid the naturalistic fallacy and resolve the argument from evil?

First let’s agree with Harris that however we cross the is/ought divide, it’s unavoidable (even if there isn’t some sort of deductively arguable logical jump). The fact remains that to exist, and particularly to function in this reality, to “creatively avoid the dissolution of the metabolic process that moves through us”, we somewhat paradoxically have to move from is to ought. Actually, it’s pretty much impossible to think of any action or ethical choice that isn’t somehow defended with an argument from what is the case. And that ironically even applies to the argument that one can’t get from is to ought: i.e. “It is the case” (presumed statement of fact) that “you can’t” (normative prescription) get from is to ought. Likewise, those who use the is/ought conundrum to eschew attempts at a coherent meta-ethical theory are still bound by the unavoidable connection of is to ought. For example, a common tactic for resolution is, we “can’t get from is to ought” (presumed statement of fact), therefore “I as an individual must create my own Meaningful good life” (normative prescription). So, since it is still the case that descriptive statements are obviously different than prescriptive statements, then how do we best resolve this conundrum?

Scientific pantheism’s answer lies in the understanding that, since we have to move from is to ought anyway, then it pragmatically is the case that we are best served by assuming/accepting (or more importantly having faith in) the belief that valuing what is most generally descriptively true (the universe as a whole and the universal laws of physics), is what ought to be. What is most generally true should thus be at the top (the highest value) of what then becomes the most coherent/unified (since the whole universe is included), and thus most functional, resulting ethical hierarchy (the key word here is generally). To the degree that we are not nihilistic or suicidal we all do this anyway, when we assume, and thus choose to live as if, our existence in this reality is worth it. I.e. reality is good, or, i.e. reality is the good, and thus worthy to be in. It’s the specifics that get you. Only a minority subset of specific things or actions within reality are, or can be, evil. In general, to exist and flourish through life’s occasional tribulations, we must believe or have faith that existence (reality (or the pantheistic god)) is generally good, or even wonderful and thus even worthy, in general, of worship. Subjectively, to function we must have faith that goodness is a kind of primary quality in general in reality, and that evil is a secondary quality that only applies to a certain minority of specifics. Note that this argument also explains (to pantheists) why parochially anthropocentric humans have felt compelled to invent the theistic god who is to be worshiped as benevolent and universal, even though evil events obviously still happen. This resolves the argument from evil: tidal waves and plagues may kill millions, supernova radiation bursts may take out planets, but to function, and not just give up and die, we must have faith that reality as a whole is still good/worth it. This idea of resolving the is/ought question with a general versus specific component isn’t such an unusual idea; virtually all of the things or actions that we subjectively choose to call good or bad are not wholly so. You may love your spouse, family, job, country, or home in general, but there are still probably specifics about all of these parts of your life that you don’t like, or even hate.

So, as a corollary ethical position, the naturalistic fallacy really only occurs when one attempts to move in a specific instance from is to ought in a way that is out of hierarchical accord with what is more generally the case. For example, if you as a life form choose to eat something specific that is altogether natural, but that will still kill you, then you are also choosing to go against acting in accord with what is the more general definition of life (a dissipative structure organized around the ability to avoid its dissolution).

But have we actually resolved the is/ought conundrum? Well, if, as explained above, we can’t help but somehow resolve it by any action or non-action we “choose”, then the only real choice isn’t if we resolve it, but how. And the scientific pantheists ethos of saying that what ultimately is, is what ought to be, is the most holistic, and thus most coherent and unifying, and thus has the most reasonable hierarchical value system (see the mandala particularly the top of the mandala, in the first essay above).

So some may be wondering, considering the points above, how is one to resolve G.E. Moore’s analytical “open question argument” that “proves” how the is/ought problem is intractable?

Let’s review Moore’s argument:

Premise 1: If X is (analytically equivalent to) good, then the question “Is it true that X is good?” is meaningless.

Premise 2: The question “Is it true that X is good?” is not meaningless (i.e. it is an open question).

Conclusion: X is not (analytically equivalent to) good.

Simple: The points above are not arguing that X (the universe) is analytically/logically or objectively equivalent to good. Rather, as the left side of the pantheist mandala shows, it is assumed that on the path to wisdom, most humans can subjectively recognize that it is spiritually enriching and pragmatically useful to accept that reality as a whole (the universe) is not only good, but the greatest good in general. That is, once again, because of the following two main scientific pantheist points; they may be great points, but it’s true that you are not analytically compelled, rather you can simply subjectively choose to agree with them, or not:

1. Reality as a whole is big enough, and in general awesome, beautiful, comprehensible AND mysterious enough (and the ego is small, ephemeral, and isolated enough) that cultivating reverential oneness with reality as a whole is profoundly spiritually enriching and motivating. Indeed you can argue that it is the most profoundly spiritually enriching and motivating thing, simply because it includes everything that you could care about.

2. It is pragmatically useful to call reality as a whole THE Good because, since everything is included in reality as a whole (including an instructive hierarchy of the sciences), a holistic/unified coherent meta ethos can then be derived that is in accord with this reality, because by definition there is no reality outside of it with which there could be conflict.

i.e. Subjectively, what ought to be the case most generally, is what is objectively the case most generally.

Ok, so in the end, have we really and completely resolved the is/ought conundrum? Honestly? No. And it is important to be honest about this: like pretty much everything in this reality, resolving the is/ought conundrum is only a matter of degree. Sam Harris may claim that since no sane person wants a universe with maximum suffering, then it’s ok to say that it’s a fact that we subjectively want well being, and therefore according to Harris it’s OK to make the jump to founding a meta ethos on “maximizing of well-being of conscious creatures”. Alternatively the scientific pantheist claims that cultivating faith that the universe as a whole is in general good, and thus The good, will create the most coherent and unified meta ethical system. But these, and any other founding prescriptive appeals, are more rhetorical than “ultimately” reasonable. The individual trying to choose an ethical system will ultimately choose based simply on how much they happen to care subjectively and emotionally about, say: well-being and avoiding suffering first, or about functional coherence and unity first.

So, as a final rhetorical pitch: if you are impressed by the success of science’s ability to enhance well-being, then remember: modern scientific theories are empirically and functionally deemed most successful only if they can first present us with a more inductively coherent and unifying (reasonable) understanding of reality. i.e. Don’t put the cart before the horse!

Also, let us remember that deductive certainty is impossible in non-axiomatic systems, such as reality, leaving inductive reasoning as the primary route to (probabilistic) knowledge of such systems. And Harris’s boot-strapped moral system is unrealistically axiomatic.

And for fun, here is a lovely article: on Induction: (Distinguishing Generalizations from Universals).

9. Bootstrapping is a unscientific Aristotelian process, and Harris bootstraps “well-being”

9. Bootstrapping is a unscientific Aristotelian process, and Harris bootstraps “well-being”

Sam Harris’s logic for why the well-being of conscious creatures is primary is, bootstrapped, linear, and thus Aristotelian, which is out of accord with how modern science progresses.

Here is Harris’s central/founding argument for his meta-ethos. Again, it’s linear, Aristotelian, deductive, and syllogistic:

Premise A: Surely we can agree that a universe where ultimate suffering occurs would be a BAD universe.

Premise B: If we agree that ultimate suffering universe is bad, then we should agree that suffering is the bad.

Conclusion: Moving away from suffering (towards well-being) is the GOOD.

It’s true that Harris wants to apply science to achieving well being, but he didn’t apply science to prescribing well being. In scientific pantheism science can be applied to prescribing well being once one simply accepts the body of knowledge arrived at via science, normatively (where the more generally applicable the scientific knowledge is, the more prescriptive it becomes). That is to say, the prescription for the good is to simply act in accord with the ontological hierarchy of the sciences as if it is an ethical hierachy of prescriptions: what science says is the case from the most general (the laws of physics) is ethically dominant, and on down the hierarchy to what it means specifically to be a human, down to what it means to be oneself. That prescription will evolve and improve as the sciences improve.

In modern science there are no certain first premises. Thus scientific knowledge isn’t static. Indeed there is no certainty. But science can advance, and it advances in a circular (or more accurately, a spiraling) fashion, via: data gathering, inductive hypothesizing, deductive tests, then and more data gathering. Its a circular (but hopefully entire universe encompassing) dialectical process.

The sci-pantheist mandala shows the centrality of the induction/deduction dialectical process, which thus enables truth AND value to be arrived at via an ever advancing (often asymptotically advancing) dialectical process. Which, not coincidentally, is the way nature can be observed to work in, say, the birth and maturation of a human consciousness.

So regarding Harris’s syllogism, “Premise A: Surely we can agree that a universe where ultimate suffering occurs would be a BAD universe.”, yes, most sane people would surely agree with this premise. But trying to bootstrap an ethical world view from this parochial (non-holistic) premise will lead to about as much confusion as bootstrapping an ethos from, say, “genocide is bad”. Sure, most sane people would agree that genocide is bad, but there is a lot to consider, when acting in this reality, that hasn’t got much to do with genocide. . .