18. What is Life?

18. What is Life?

The foundational meta-ethical prescription/argument of scientific pantheism is: Reality in general (the universe) is the good, so act in accord with reality. As one does this an ethical hierarchy forms, from what is most generally the case down the hierarchy to what it means to be an individual. And at perhaps the halfway point in that hierarchy is the prescription to act and be in accord with the best scientific definition of life. i.e. For a scientific pantheist accepting that this material reality is the good, acting in accord with the definition of life in a crucial sense also becomes the Meaning (purpose) of life.

So, getting the definition of life correct, scientifically correct, becomes a very big deal, ethically. As stated above, this is the definition:

Life is: an individuated metabolic process (thermodynamic dissipative structure) that has become organized around the ability to creatively* avoid its own dissolution (through sensing and responding to its environment).

*The concept of creativity, as it is used here, doesn’t necessarily require conscious intent. Creativity can be here defined as, any natural process (algorithm) where functional order is formed out of chaos, and at some point in that algorithm a random variable is interjected such that the new order is relatively unique. Some examples: The root ball that any tree in a forest creates is unique. The particular exact path any bee creates to get pollen and nectar out of the flowers in a meadow is unique. A new species created via natural selection is unique.

*The concept of creativity, as it is used here, doesn’t necessarily require conscious intent. Creativity can be here defined as, any natural process (algorithm) where functional order is formed out of chaos, and at some point in that algorithm a random variable is interjected such that the new order is relatively unique. Some examples: The root ball that any tree in a forest creates is unique. The particular exact path any bee creates to get pollen and nectar out of the flowers in a meadow is unique. A new species created via natural selection is unique.

And why this particular definition of life? Because this definition simply explains not just what all of life is in terms of its characteristics, but also leads us to why and how life came into being and exists (in terms of physics, which applies, beyond earth’s biosphere, to the entire universe). Thus it is the best definition because it transcends mere description to provide an accurate theory of life:

- Via the 2nd law of thermodynamics, energy dissipates.

– Matter in some configurations can be reactive as energy dissipates through it, thus dissipative structures can form.

- Over time, as energy moves through dissipative structures, those structure that are more resilient will be naturally/randomly selected for.

- The most resilient dissipative structure(s) would be organized around a creative process (see comment* in italics above) that allows the structure to change to avoid dissolution. Once this happens there is life.

In science an empirically sound theory is a profound step up from as an explanation, from a simple description of the observed data. Compare the explanatory theory above to the complex and puzzling standard mere descriptive attempts at an “explanation” of life in this lecture: (lecture), or in the “definition” below:

Wikipedia: ”The definition of life is controversial. The current definition is that organisms are open systems that maintain homeostasis, are composed of cells, have a life cycle, undergo metabolism, can grow, adapt, to their environment, respond to stimuli, reproduce and evolve.”

Unlike the Wikipedia definition, which just lays out the characteristics of earthly life, the definition in bold above ties the characteristics together by explaining them in terms of the laws of physics that gave rise to life. So, again, given an open thermodynamic system, where energy is constantly being added, and given that same system has a sufficiently complex and reactive stew of chemicals such as existed on the earth’s surface: complex dissipative structures will continuously form. And, thus (given enough energy, matter, and time) chance and simple chemical dissipative structural evolution has inevitably (on earth at least) caused a dissipative chemical structure to become organized around the ability to creatively avoid it’s own dissolution (life). And that definition also helps us understand life in some uncommon ways:

For example, the definition leads us to the unexpected conclusion that life isn’t so much characterized by change as it is by stability. Once a dissipative structure that can creatively avoid it’s own dissolution comes into being, and if the energy supply continuous (our sun), then that structure may become far more stable/resilient than other dissipation structures. For example, on the surface of this earth, fires and rivers are thermodynamic structures (which dissipate the sun’s energy) that come and go. Coal or wood fires may last weeks or even years, and rivers may last for millions of years. But the single dissipative structure that is life has been around for billions of years.

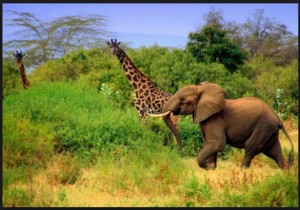

Another uncommon way to understand life thus defined: all earthly life is one; as in, it is all one dissipative three to five billion year old structure. It is merely our egoistic myopia that misguides us, as “individuals”, to think that we are truly separate life forms. We are not. We are one dissipation structure, connected, via reproduction to the original cell. Reproduction doesn’t so much make us separate (in a way that would be valid for the most functional/scientific definition), as it is simply a way (via reproduction and natural selection) that life (the dissipative structure) creatively avoids dissolution. The analogy that may help make this clear is multi celled organisms: “separate” organisms are an individuated part of the whole dissipative structure that is life, in an analogous way to cells being an individuated part of a multi-celled organism such as yourself. Individual cells may come and go (live and die), but their death is relatively irrelevant. The greater organism remains. So, likewise, organisms may come and go but the dissipative structure that is life remains. Although one may feel diminished as a mortal individual by this realization, one can also feel elevated by the realization of one’s collective identity as part of a billions of years old structure. Try contemplating that next time you are out walking in a forest. And Einstein said that is our “task” anyway, right? Life, which we are a part of, properly defined, is immortal! Well, billions of years old isn’t immortal, but from the perspective of an average human’s 80 year “lifespan” (<<Ha!) it might just as well be. . .

Another uncommon way to understand life thus defined: all earthly life is one; as in, it is all one dissipative three to five billion year old structure. It is merely our egoistic myopia that misguides us, as “individuals”, to think that we are truly separate life forms. We are not. We are one dissipation structure, connected, via reproduction to the original cell. Reproduction doesn’t so much make us separate (in a way that would be valid for the most functional/scientific definition), as it is simply a way (via reproduction and natural selection) that life (the dissipative structure) creatively avoids dissolution. The analogy that may help make this clear is multi celled organisms: “separate” organisms are an individuated part of the whole dissipative structure that is life, in an analogous way to cells being an individuated part of a multi-celled organism such as yourself. Individual cells may come and go (live and die), but their death is relatively irrelevant. The greater organism remains. So, likewise, organisms may come and go but the dissipative structure that is life remains. Although one may feel diminished as a mortal individual by this realization, one can also feel elevated by the realization of one’s collective identity as part of a billions of years old structure. Try contemplating that next time you are out walking in a forest. And Einstein said that is our “task” anyway, right? Life, which we are a part of, properly defined, is immortal! Well, billions of years old isn’t immortal, but from the perspective of an average human’s 80 year “lifespan” (<<Ha!) it might just as well be. . .

Thus, meta-ethically, if we want to be in closest accord with this reality, we as living organisms should choose to be in closest accord with the definition of life. So we should care about doing our part to keep the, thus far “immortal”, metabolic process going (or dissipation structure) as far into the future as we can influence. How? Well that is a complicated question, but normally it’s probably most economical, pragmatic, and evolution-airily psychologically satisfying to start locally with maintaining the metabolic/dissipative process in and through ones’s own body. Because, if nothing else, it’s obviously functionally easier to breath, eat, and provide clothes and shelter for yourself and your family first before you can even have the ability to do the same for the larger world. The old adage, “think globally, act locally”, still makes sense.

Finally, as an aside, the definition above helps us answer the question: When would or could A.I. or a computer viruses be alive? They could be, and considering the definition above, science fiction may help us out with knowing when the threshold might be crossed. Why would most people consider HAL or the women in Ex Machina alive? Well they are dissipative structures, and when we conclude that they are actively organized around creatively avoiding their own dissolution we empathize that there is a fellow life form, and thus we are conflicted even when they attack a human. Particularly if that human is rather bland and passive (as in 2001), or a sociopath (as in the robot’s creator in Ex Machina).