10. The scientific pantheist’s position on the well-being of non-human conscious creatures.

10. The scientific pantheist’s position on the well-being of non-human conscious creatures.

Though the two systems of ethics (pantheism and utilitarianism) skew, and dangerously so, it is important to reiterate that the two systems only skew; they are not diametrically in opposition. There are some profound reasons why an ethically consistent scientific pantheist should value non-human conscious creature’s well-being. The reasons are listed below, in no particular order:

Though the two systems of ethics (pantheism and utilitarianism) skew, and dangerously so, it is important to reiterate that the two systems only skew; they are not diametrically in opposition. There are some profound reasons why an ethically consistent scientific pantheist should value non-human conscious creature’s well-being. The reasons are listed below, in no particular order:

A. On the left, subjective, side of the mandala a scientific pantheist comes to value non-human conscious creatures simply as the pantheist values all of reality. That’s because our hunter gatherer brains, evolved to function on a planet surrounded by other life forms, can (often, but not always) easily feel, when immersed in the natural world, that non-human conscious creatures are a mysterious, awe inspiring, and sacred part of nature as a whole.

B. On the middle right side of the mandala the pantheist values all conscious creatures well-being because, objectively, there is a reciprocal altruistic benefit to valuing them as part of the synergistic ecosystem that we need to maintain for survival, i.e. to be in accord with the definition/meaning of life.

C. To the scientific pantheist,

since we humans value our conscious selves,

and, since we can empirically recognize that other species have consciousness in varying degrees,

part of cultivating civilization enhancing concern for our fellow humans,

means that we need to work at cultivating empathy for consciousness, such that wherever we find it we value it.

i.e. There is a reason why psychologists tell us that psychopaths, sociopaths, and narcissists are indifferent to the suffering of animals.

D. Beyond the immediate pragmatic justification of valuing of the well-being of conscious creatures, there is another reason why a thriving sustainable advancing human civilization is a critical part of caring about earthly life as a whole. It is that human civilization is surely earth’s best chance at earthly life staying in accord with the definition of life into the indefinite future, and it is kind of hard to imagine biological homo sapiens existing in the universe without at least some of our fellow species. So, it is likely that, in earth’s past and future history of life, only humanity and our civilization may be able act as the ark species, that enables earth’s life to go off planet and into the galaxy. To be in accord with the definition of life, the scientific pantheist sees it as a mandate, therefore, to spread, not just humans, but earth’s life (potentially millions of earth’s species) gracefully and benignly in accord with the scientific definition of life, to worlds (preferably here-to-fore un-inhabited worlds) throughout the galaxy, and possibly beyond, even after this earth has been encompassed by the sun.

11. Isn’t biological survival an inherently selfish concept, and won’t a mandate to reproduce exacerbate overpopulation?

11. Isn’t biological survival an inherently selfish concept, and won’t a mandate to reproduce exacerbate overpopulation?

Couldn’t one say that, it’s in the inevitable nature of natural selection (a la Dawkin’s Selfish Gene) that in the scientific pantheist’s moral hierarchy, putting survival above well-being must logically lead to some sort of social Darwinist ethos? No.

Why? Because for individual modern homo sapiens, a simplistic “selfish gene” survival of the fittest strategy is a poor survival strategy. If such a strategy were accepted on a society wide level, most of our (your and my) personally unique genes won’t be the “fittest” genes, and thus they will die out via natural selection. By now humans, living and successfully surviving within the benevolent confines of civilization, should know that, due to the multitude of synergistic benefits of human social interactions, the best survival game for modern humans to play is a positive sum game. And short shortsightedly selfish gene games tend to be zero sum games. (see game theory)

So, you may say, “That may all be well and good, but humans simply are so genetically shortsightedly selfish, that they can’t change, to the degree that any enlightened-self-interest-philosophy is practical enough to even bother with”. That answer to that is that human cultural influence can be extremely powerful. Consider for example, the difference between the Jains (an ancient vegetarian culture so peaceful and non murderous that they wear face masks and have brooms when they walk so that insects can be gently removed from their path, rather then stepped on or inhaled), and the Aztecs (who made the mass sacrifice of humans, via cutting the heart out, a central part of their culture). We don’t know if humanity as a whole can sufficiently follow an optimum ethos such that civilization destroying selfish genes aren’t selected for, but we do know that homo sapiens is young (and thus relatively untested), and very culturally malleable.

So, you may say, “That may all be well and good, but humans simply are so genetically shortsightedly selfish, that they can’t change, to the degree that any enlightened-self-interest-philosophy is practical enough to even bother with”. That answer to that is that human cultural influence can be extremely powerful. Consider for example, the difference between the Jains (an ancient vegetarian culture so peaceful and non murderous that they wear face masks and have brooms when they walk so that insects can be gently removed from their path, rather then stepped on or inhaled), and the Aztecs (who made the mass sacrifice of humans, via cutting the heart out, a central part of their culture). We don’t know if humanity as a whole can sufficiently follow an optimum ethos such that civilization destroying selfish genes aren’t selected for, but we do know that homo sapiens is young (and thus relatively untested), and very culturally malleable.

Regarding overpopulation and over-consumption:

If living correctly (in accordance with the definition of life) means maintaining your genes as far into the future as you have influence, then what about the resulting mandate, to reproduce, exacerbating existing overpopulation and the earth’s taxed resources?

It could exacerbate overpopulation (and over-consumption), but only if reproduction and resource consumption are unwisely pursued as a zero sum game. Regarding the definition/Meaning of life (discussed in the “Home” article above) and overpopulation, the situation is complicated, and several crucial points need to be understood:

It could exacerbate overpopulation (and over-consumption), but only if reproduction and resource consumption are unwisely pursued as a zero sum game. Regarding the definition/Meaning of life (discussed in the “Home” article above) and overpopulation, the situation is complicated, and several crucial points need to be understood:

- To be in accord with the definition of life one should want to maintain the metabolic process that moves through us as far into the future as we can predict. And, thus, scientific pantheist morality prescribes that civilization should be structured such that the future (even the distant future) becomes more predictable, and thus predictably sustainable. I.e. the rapid rate of change in the modern world (of which mindless exponential population growth has been a central example), which is based on relatively short term hedonistic and/or utilitarian values, is too fast. Currently, it is very much not structured with the long term survival or sustainability of civilization as a top priority.

- We should be thinking about (and acting to be in accord with) the optimum sustainable human population and lifestyle of/for the earth. We need a vision for the optimum long term population, not just for the coming decades, but for the coming hundred million or more years. Thoughtfully, sustainably, and gracefully taking earthly life into space may be the greatest gift homo sapiens can hope to offer our biosphere and the universe as a whole, but, if we love our species, and we love the gift of existence on this beautiful earth, why shouldn’t taking care of our original home also be a priority?

- Having a successful future means being mindful and respectful of the lessons of the past. We definitely can and should have modern civilization and continue to carefully pursue the latest technological improvements for the human situation. But, we evolved on this planet, and we evolved into homo sapiens as hunter gatherers. Thus, there are deep and crucial “spiritual” reasons for respecting, revering, and maintaining much of this planet as wilderness; enough wilderness, for earth’s wild species to thrive, but also enough such that every human can experience wilderness without destroying it. As descendants of hunter gatherers, we are best able to cultivate the passion for existence necessary to take on the travails that come with existence, if we have the wild nature of our home within which to become aware of the “sacred”, to connect with “God”. Thoreau, Annie Dillard, and John Muir, and Edward Abby, are “prophets” of this spiritual need/requirement. Check out this essay by Abby (and start on page 236 if you are busy): Link

- Cramming as many humans onto the planet as the latest technology will allow us to feed and shelter (the Malthusian maximum), is not wise. It is dystopian, if only because of the spiritual need (mentioned in the point above) that would be unmet. Thus, the common argument that, at this moment in history there are enough resources for everyone to eat, so therefore we don’t have an overpopulation problem, is immorally shortsighted.

Therefore: the proper way to consider the overpopulation and over consumption issues aren’t, “do we have too many, to few, or the right amount of people and stuff right now?” It’s, what is the optimum number of people and median consumption rates for this earth for the next hundred million years? True, future generations and cultures may come to a different decision regarding the optimum number and median consumption, but we and our descendants should none-the-less strive for that long term vision.

So, once the optimum population number is decided upon (ideally via egalitarian consensus, or at least via democratic vote) how do we humanly (positive sum game) arrive at and maintain that number?

First, if at all possible, children should never be made to suffer if their parent’s reproduce more than is fair. So, since it is hard to involve the law, in consequencing parents without making children suffer, ideally instilling cultural mores and taboos around birth control and family planning are the sanest, primary, and first ways to arrive at and maintain an optimum population.

Second, considering the definition/Meaning of life, reproduction is like voting:

-It shouldn’t necessarily be required, but it should feel like a responsibility for anyone who wants to, and thinks they are up to, respectfully accepting the nature of existence.

- Since it’s part of the very definition/Meaning of life, reproduction to maintain the metabolic process that moves through us is literally as fundamental as breathing, and as such should be considered as fundamental a right as breathing.

- Just as every citizen should have the vote, but no one should vote more than their share, every one should have the right to reproduce, but once the (positive sum game) optimum population is agreed upon, at least democratically, no one should have more children than their equal share. I.e. two parents should have no more than two children (unless of course there are natural twins, triplets, etc).

Assuming it can be arrived at humanly, what is the optimum population for the earth? That is a fairly subjective question, but I (the author) would vote for one billion, because:

Assuming it can be arrived at humanly, what is the optimum population for the earth? That is a fairly subjective question, but I (the author) would vote for one billion, because:

- Currently there isn’t even close to enough wilderness for long term ecological balance and sustainability, for our “spiritual health”, or, simply, for wildlife. For example, this statistic is insane and evil: humans and our domesticated mammals make up 96% of all mammalian biomass on the planet. Despite the immoral prerogative we have taken upon ourselves of so diminishing the natural world, how can we justify leaving such an impoverished world to our poor descendants?

- Our current civilization is precariously (even insanely) based on the use of unsustainable resources, the most obvious being fossil fuels.

- One billion people is enough people that we could have at least a few cities that are big enough that, no matter how much an individual may desire to be around a lot of people, there would still be enough people (we reached the 1 billion mark in 1804). There could still be a lot of cultural diversity. And, there is no way any one person could ever come close to knowing a billion people.

- One billion people would surely supply enough creative individuals for sustainable and enjoyable technological and artistic innovation. And there would surely be sufficient economies of scale such that eventually humanity could sustainably begin to “colonize” space.

- With one billion people, that is a large enough number that it would be hard to for most traditional disasters, volcanoes, plagues, etc. (at least) to wipe us out.

- One billion is a nice round base-10 number!

So, what about the people who can’t or don’t want to have children? Like not being able to or not wanting to vote, it is a handicap. It is generally naturally and instinctual-ly easier, to find the motivation to be invested in the future, when your own progeny (see post on selfishness) can create the direct path forward for the metabolic process that moves through us.

But, like most handicaps, it doesn’t have to rob one of one’s reason for living. There is much that can be done to remain in accord with a scientific pantheistic ethos. In this complex reality values must fall into a hierarchy. We can prioritize (within the hierarchy) as individual circumstances may require. As one descends the hierarchy shown on the right side of the mandala, the rules for life are roughly akin to Maslow’s “ascending” hierarchy of needs. I.e. generally we must be able to feed, shelter, and reproduce ourselves first, before we can have the capability to work for a sustainable future/path for our descendants. So, for those who have no direct descendants (fending for whom is actually relatively similar to fending for one’s self), personal energy can be freed up for expanding one’s efforts towards the survival of an expanding circle of genes that one shares with relatives, the human race, or the survival of our marvelous modern niche (civilization), or of biologically related species, or of ecologically and “spiritually” necessary species, or of earthly life as a whole, of the material niche that is this earth, and of the future niche that is space.

And what about over consumption? Well, rules of thumb such as “no more that two child children per citizen” are much harder to come by, but for an individual citizen, once the basics for a healthy and happy life span are attended to, a culture and democratic government should be continuously cultivated such that, one willfully will work and tithe, and/or allow oneself to be taxed, to wisely benefit and maintain that which is larger than the self. With that in mind, we can reasonably say that, in general, we citizens of the developed world are too “materialistic” by, probably, an order of magnitude. We can spend more time in nature, more time with the earths millions of other life forms, more time socializing, more time appreciating and creating art, live in much smaller homes, use or own automobiles far less, own far fewer possessions, throw far less away, eat less and more simply, etc..

Finally, for anyone who has read this essay, the following question has probably arisen: isn’t the vision for the future, elucidated above, too Utopian? And the corollary question: even if it were somehow possible to briefly create a human culture where the majority wanted to follow the vision elucidated above, couldn’t and wouldn’t a small differential of selfish individuals inevitably still fuck it up? Well, yes, the future is uncertain, but in the terminologies of biology and evolution: if a specie’s niche is correctly maintained by the majority of organisms, then individuals who act out of accord with the survival parameters of the niche will not be naturally selected. e.i. For humans, civilization (our niche) can create and have effective, but humane, ways of dealing with criminal behavior. And, just because a path may be difficult, and the risk of failure great, does not necessarily mean that there are other options; if we love this reality/universe enough that we wish to be in accord with it, then there is a prescribed path. Whether it is a difficult path or not is of secondary relevance.

12. Aren’t Utilitarians concerned about existential threats anyway?

12. Aren’t Utilitarians concerned about existential threats anyway?

But, aren’t utilitarians concerned about existential threats anyway? No, not really. . .

Well, kind of, sometimes. . .

The typical utilitarian ethos isn’t. It is exemplified by such influential contemporary figures as Sam Harris; but also Peter Singer, the philanthropist Bill Gates, Steven Pinker, and Jordan Peterson (to the extent that Peterson could be called a utilitarian). And that ethos is compelling because of its direct though short sighted “low hanging fruit” approach to maximizing well-being. The low hanging fruit approach largely ignores, or under values, or simply dismisses, existential threat concerns. And if you want to see how compelling the low hanging fruit approach is, this video of Peter Singer’s powerful Ted talk on “effective altruism” is exemplary. And bear in mind that the largest portion of philanthropic energy ever directed, beyond short term selfish concerns, by an individual, was made in accord with Singer’s version of utilitarianism, by Bill Gates.

Compare the painfully emotive and powerful video of Singer’s (link above) to this relatively dry video of Nick Bostrom’s (a key “utilitarian” (more or less) who is concerned primarily with existential threats). Watch them speak and you will see why Singer’s ethos holds sway.

Further, here is Sam Harris’s podcast where he interviews Bostrom, and is puzzled by the “esoteric” nature of Bostrom’s concern about humanity’s future. Check it out, starting at minute 13:00.

Bostrom makes the utilitarian argument that, a little energy used as insurance in preventing even unpredictable/hypothetical existential catastrophes likely has a huge payoff in future well lived lives (well-being). And it’s a payoff that is statistically many orders of magnitude larger then the payoff one gets from Singer’s and Bill Gates’ “effective altruism”. But he isn’t more popular in utilitarian circles because his values are too abstract for our “evolved” human psychology. As Stalin said, “one death is a tragedy, but a million deaths is a statistic.” This is why many charities, and Singer’s video, show pictures of a single real and present distressed child when eliciting aid. Even though Singer notes, and even focuses on, the irrationality of Stalin’s maxim, Singer still plays to it; the low hanging fruit is that, even though he may focus on the suffering of one child, it is a very small intellectual/rational jump to acknowledge the immediate and current suffering that is occurring now all over the world. Bostrom’s task is far more difficult: getting our primitive hunter gatherer minds to give a toss about maximizing well-being and minimizing suffering of, as yet non-existent, beings into the distant future. Indeed, the future isn’t written yet. Also, as Harris and other utilitarians have pointed out, from the perspective of “well being” a reality without us, without consciousness, doesn’t matter. So, in the calculus of well being, a future with no humans, or even no sentient beings at all, and thus no suffering or well being, would be at worst neutral from the perspective of desirability, and it would also involve no unpleasant uncertainty or work as to how to improve the well being to suffering ratio. But the scientific pantheist will always care for the future, because creatively working for survival, in perpetuity, is what life in this universe does.

So, as a matter of fact Bostrom’s utilitarianism as about as popular and influential as the pro extinction “antinatalism” “negative utilitarianism” of figures such as David Benatar (here’s an interview with Benatar). From a scientific pantheist’s perspective, Benatar’s fairly “persuasive” arguments also exemplify how the “esoteric” and emotionally/empathetic-ally unconvincing well-being calculus of utilitarianism can become what is likely to be disastrously disconnected, from an emotional and empathetic state which would lead to individuals truly wanting to act in accord with the scientific definition of life. And, in the interest of frankness and honesty, it should be said that from the scientific pantheists perspective Benatar’s ethos is also obviously profoundly and disastrously evil.

Benatar’s, Bostrom’s, and Singer’s vastly divergent versions of utilitarianism also give lie (or at least pause) to Harris’s assertion that science can be relatively easily applied to something as subjective as well-being.

The left side of the Mandala leads up a path, that’s subjectively more visceral and rational, to abstract meta values (than most of utilitarianism’s, which are for human psychology). True, when Singer employs images of the easily preventable suffering of a single child, that may be more immediate and viscerally effective than the scientific pantheistic path (starting at “awareness of the sacred”) might be. But that depends on the art and rituals that our culture develops, and the scientific pantheist approach is more reasonable and scientific, and it is more viscerally appealing then the utilitarian ethos of Bostrom and Benatar (which are just as “reasonable” as Singers’s).

13. AI (Artificial Intelligence and Scientific Pantheism)

13. AI (Artificial Intelligence and Scientific Pantheism)

A scientific pantheist by definition loves the natural world. So a pantheist should be profoundly cautious (at a minimum) regarding the creation of general AI. If you haven’t put much thought into AI, here is a grim but excellent primer on the dangers (link). But beyond the risks, general AI, if developed, would surely represent the greatest technological creation in human history. It would be the ultimate technology, what Ray Kurzwell calls the coming singularity. However, pantheism is predicated on the belief that this reality, in which we humans evolved into being and that we physically inhabit, is wonderful to the degree that it is sacred. So why should we hate natural reality and our natural lives so much that we would wish to alter it, and/or our lives in it, unpredictably and out of all recognition? Some improvements are fine, sure, but why do we need a “singularity” that could completely change human/our existence? Why? What is compelling us to desire something like that, or to even passively allow it to happen?

A scientific pantheist by definition loves the natural world. So a pantheist should be profoundly cautious (at a minimum) regarding the creation of general AI. If you haven’t put much thought into AI, here is a grim but excellent primer on the dangers (link). But beyond the risks, general AI, if developed, would surely represent the greatest technological creation in human history. It would be the ultimate technology, what Ray Kurzwell calls the coming singularity. However, pantheism is predicated on the belief that this reality, in which we humans evolved into being and that we physically inhabit, is wonderful to the degree that it is sacred. So why should we hate natural reality and our natural lives so much that we would wish to alter it, and/or our lives in it, unpredictably and out of all recognition? Some improvements are fine, sure, but why do we need a “singularity” that could completely change human/our existence? Why? What is compelling us to desire something like that, or to even passively allow it to happen?

It has been argued that AI is inevitable due to the nature of the free market. But we humans create the damned free market. Why are we currently so passive that something as utterly existentially important as AI doesn’t stir a sufficient number of us to effective action, stir us to take charge of what we are doing? Why don’t we deliberate and choose to act decisively, to honor and revere the profound, awesome, and mysterious gift of this existence? Haven’t enough people watched 2001 A Space Odyssey, to understand the logic that to be worthy of wholesome advancement in the human situation, we must first show that we are in charge of our own damned tools, and not vice-versa? Could it be that supernatural religion on one hand, and the dominant secular ethos of utilitarianism on the other hand, has us so pathologically focused on our ego’s “well-being” that we have become indifferent to the well-being that arises in simply being in reality? Doesn’t this pathology need to be healed, first? Else-wise aren’t we inevitably doomed by our hatred for the way things currently are, to follow a hate (implicit in our passivity) driven road to a likely monstrosity, which is the most natural outcome of something born of hate? After all, would love create a desire to turn this reality, from which we are born, upside down or inside out?

14. Harris’s ethos exacerbates of the separation of consciousness from reality.

14. Harris’s ethos exacerbates of the separation of consciousness from reality.

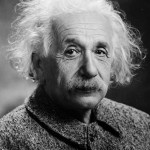

Harris’s ethos is an exacerbation, instead of alleviation, of the separation of consciousness from reality that Einstein (and religious sages) spoke of.

To the scientific pantheist the “transcendent/numinous” awareness of, and awe at, the order and mystery of reality is more important than the relatively solipsistic and hedonistic-ally prone value structure that comes from focusing on “well-being”. As Einstein said, and as Harris as a practitioner of meditation is aware, the ego’s separation from reality is a kind of angst ridden delusion. So, isn’t it appropriately Zen (or superficially paradoxical) to ask that, “Isn’t focusing ultimately on (and loving) oneness with reality as a whole spiritually/existentially better for the well-being of consciousness, then simply focusing on (and loving) the well-being of consciousness”?

15. Do humans naturally care about reality more than the well-being of conscious creatures?

15. Do humans naturally care about reality more than the well-being of conscious creatures?

But do humans naturally care about reality as a whole more than the well-being of conscious creatures? And if not, and if that is what we should do (as per the main article above), how do we make it happen?

No, from an instinctual perspective, we naturally do not.

No, from an instinctual perspective, we naturally do not.

The navel gazing obsessive temptation of a human to care inordinately about him or herself, their family, their tribe, humanity only, or, at most, conscious beings as a whole over reality as a whole, to the possible severe civilization collapsing, ironic detriment of conscious beings, is something we have long been aware of.

Indeed, as Maslow pointed out, since the metabolic process that moves through us is most efficiently served via the self first, our selfishness is biologically understandable and somewhat forgivable. Pragmatically it is generally way easier to first breath for yourself, feed yourself, clothe yourself, etc.. And that’s often before you even have the physical ability to tackle larger issues. There is also of course the fact that evolution exacts a strong selective pressure for simple selfishness.

However, arguing that since we naturally care more about ourselves, then we should care more about ourselves (or, at most, care about the well being of conscious creatures (that are thus like ourselves)) is a legitimate example of the naturalistic fallacy. And, as was pointed out in is/ought post #8, the most pragmatic, consistent, and reasonable way to deal with the naturalistic fallacy is to accept nature/God in the most general sense, and then subordinate lesser/more specific natural proclivities in accord with the hierarchy of the sciences.

Additionally, once basic needs are met, an overly parochial self-focus quickly becomes impossible to maintain. That’s because ultimately, as dissipative structures, we are immersed in the changing and often unpredictable world. We must adapt to the universe because it is almost inconceivably bigger and more powerful than we are, and to succeed at that we must care about the world. To the Pantheist, God equals the World/reality. As the biblical Jesus is quoted as saying, “There is really only one commandment: Love God with all your heart, mind, and soul, and your neighbor as yourself”. Whether Jesus existed or not, to the scientific pantheist the one commandment is spot on. Loving your neighbor as yourself (as an approximation for caring ultimately about the well being of conscious creatures) for ferociously social, synergy utilizing, conscious human unity, is difficult enough. But hopefully on some level we all sense that loving “God”, loving that which transcends egoistic delusion, connecting to and being in accord with reality as a whole, is where the real game is, even though it’s may sometimes be more difficult than the narrower focus of caring for the well being of conscious creatures.

16. God – On Pantheism, Theism, and Atheism

16. God – On Pantheism, Theism, and Atheism

Pantheism: God = Nature.

Scientific Pantheism: God = Nature, as known through modern science.

Richard Dawkins, a world famous “new atheist”, famously said pantheism is just sexed up atheism. This flippant assertion is indicative of a polemically motivated atheist’s primary agenda: that the mission (regarding the subject of God) is to argue that the theist’s supernatural sentient supreme being(s) doesn’t exist, or cannot be proven to exist. The debate, between theists and atheists, is typically seen as a black versus white dual. No grey area. The atheist sees theism as delusional, and the source of dangerous irrational supernatural dogmatism, and thus bad or evil. And the theist sees atheists as dangerously and sinfully turning their back on the creator and thus a meaningful life, and thus atheism is bad or evil. So, a middle ground, or compromise, doesn’t seem to be an honest, or moral, option. In this dual Sam Harris and other significant contemporary public figures have famously sided with atheism.

In the context of this debate, it may be instructive to quote Einstein, ‘”The fanatical atheists…are like slaves who are still feeling the weight of their chains which they have thrown off after hard struggle. They are creatures who—in their grudge against the traditional ‘Opium of the people’ – cannot hear the music of the spheres.” Although he did not believe in a personal God, he indicated that he would never seek to combat such belief because “such a belief seems to me preferable to the lack of any transcendental outlook.”‘

Since Harris (another new atheist) appears to adhere to the dualistic approach on the question of God’s existence, he would likely subscribe to the argument that polemical atheists often make regarding pantheism: that for what it is that they are talking about, pantheists should choose another word than ‘God’. He would likely fail to see the point of calling nature or the universe “God”, and he’d claim that it’s merely a misleading semantics game. That, yes, pantheism is “just sexed up atheism”.

So, hypothetically, would it ever be legitimate for a pantheist to say they believe in God, without first or immediately clarifying that they are a pantheist? Well, there is certainly no point in being dishonest. So, the pantheist should clarify that they are pantheists. And yet, it is also honest to explain to atheists that there are huge and profound overlaps between the pantheistic and theistic definition of God:

A. Pantheists and theists see God as that which is the ultimate good (and the ultimate beauty, or Einstein’s ‘music of the spheres’), and that loving, revering, and acting in accord with that good/beauty is the ultimate Meaning of life.

B. Pantheists and theists see God as a source of transcendent unity. As “God” is that which is good/beautiful (or the root of goodness and beauty in this reality), and unity with the whole of reality is pragmatically useful/necessary for successful existence. The theist and pantheist see their prescription, for transcendent universe encompassing unity, as more useful than the more constrained and parochial utilitarian prescription (common among atheists) for ethical unity around the well being of conscious creatures.

C. Pantheists and theists see that not only is God profoundly understandable, but also awesome and ultimately mysterious. As Einstein said, “The most incomprehensible thing about the world is that it is comprehensible.”

D. Pantheists and theists see that God is where goodness and truth merge. Although a pantheist is likely to acknowledge that God is only good, and the Good, in general. Whereas a theist normally says God is always the Good. Which leads us to . . .

E. Pantheists and theists are OK with saying that, though we should and do mostly love God, it is also perfectly OK to fear god. From the pantheist perspective at least, although there is much to love and revere about God/nature, there is much to wisely respect and even fear; such as intestinal worms, or when tsunamis, tornadoes, asteroids, etc. are approaching. It isn’t a dualistic question of love versus fear. For the psychologically healthy scientific pantheist at least, it is mostly love (in general) with some healthy fear occasionally; when it’s rational, pragmatic, and useful.

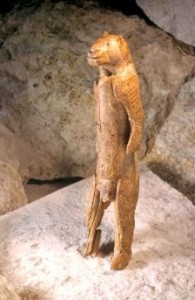

F. Regarding God’s supernatural sentience or agency, even here there is some profound room for agreement. Although the pantheist is atheistic-ally agnostic about the supernatural, they are still more likely than the atheist to sympathize with theists for being under the influence of the profound utility of seeing an anthropocentric sentient quality to God.  Even though that anthropocentric sentience for the scientific pantheist is only metaphorical. This is what Spinoza (philosophy’s most famous pantheist) meant when he non-disparagingly and empathetically referred to religion as a useful fiction. What is really meant by this? That question can be answered by asking, why has homo sapiens anthropocentrized nature from animistic paleolithic times, throughout the entire history of all of the gods of all the world’s religions, to the present?

Even though that anthropocentric sentience for the scientific pantheist is only metaphorical. This is what Spinoza (philosophy’s most famous pantheist) meant when he non-disparagingly and empathetically referred to religion as a useful fiction. What is really meant by this? That question can be answered by asking, why has homo sapiens anthropocentrized nature from animistic paleolithic times, throughout the entire history of all of the gods of all the world’s religions, to the present?

Sam Harris implicitly touches on, but fails to answer, this question when he says that, “all the concerns that we naturally have in this life are in reference to the well-being of conscious creatures”. The pantheist, theist, and animist may say yes, certainly, part of the reason people have worshiped, loved and respected rain gods, volcano gods, and oak tree gods, certainly is because; by humans propitiating them, the gods will grant favors back upon us conscious creatures.

But, atheists and secular utilitarians seem to have forgotten something fundamental and profoundly important about the nature of true love and respect: Regarding god(s), pantheists, theists, and animists implicitly understand something any successful couple knows: if love and respect are based simply on pure self interest, they don’t work very well. They aren’t genuine. Even if most altruistic acts are ultimately driven by the implicit assumption of reciprocity, altruistic acts cannot be overly calculating. Sometimes it is even wise for the ‘self’ to jump on a grenade for the common good. Indeed, the un-calculate-able/unpredictable aspects of reality are why altruism is necessary. Thus the self interested calculating lover likely won’t pay sufficient care and attention to the beloved for the relationship to work. However, the problem with necessarily altruistic love (when applied to unconscious things) is that the conscious human ego is powerful enough, and thus self referential enough, that truly loving something as unconscious as a rain cloud (or Newton’s profoundly reasonable yet ultimately mysterious universal law of gravitation) often doesn’t sufficiently work. And yet, in order to co-exist with volcanoes, trees, climate, the laws of physics, etc., we need to genuinely and deeply love and respect them.

So, how do we find a way to sufficiently love something as unlike ourselves as a volcano or as a law of physics? Well, a wise pantheist is at least sympathetic that throughout human history animists, polytheists, and theists have understandably (if factually incorrectly) anthropocentrized unconscious nature with sentience, and thus agency. And, this need for reverence (profound love and respect) of nature that transcends the self referential ethos of the well being of conscious creatures is where atheistic utilitarianism is silent and weak regarding what is a truly pragmatic necessity in this life: caring, profoundly, about the much larger non-conscious world.

This is a core reason why, for example, a well meaning secular utilitarian philosophers such as Peter Singer, and/or the world’s greatest philanthropist Bill Gates, subtly but crucially have missed the mark by parochially spending their central altruistic thrust on preventing direct suffering (certainly a worthy goal), while addressing truly existential larger environmental threats to the survival of billions of humans, human civilization, and millions of species (threats like general AI, nuclear war, bio terrorism, and climate change) has remained a secondary priority. Atheists and secular utilitarians struggle to find the path to pragmatically/sufficiently love the non-sentient world. Pantheists are much more likely to care about how our actions influence the distant future (for example), because we care about acting/being profoundly in accord with reality/nature, more than whether we as individuals will be here to directly experience the results that the trajectory of our actions cause, or not.

So, Dawkins is wrong. Pantheism is far far more than “sexed up atheism”.

17. Faith

17. Faith

Faith

Faith is far too useful a word for it to only be applied to belief in supernatural dogmas. Fuck that.

Indeed, faith in supernatural dogmas without evidence is weak faith because it is counter-factual, childish, self centered, and parochial. A much stronger faith, in the beauty and goodness of reality as discovered by rigorous science, is required to find the strength to take on the travails of existence necessary to be successful as life forms.

Faith and God. These old words come closest to a couple of the central concepts that the scientific pantheist has profound use for. Even though the scientific pantheist’s use of the words differs from the norm, they would argue that the pragmatic core of the meaning of the words “faith” and “God” is correct. And thus, the less pragmatic wholly counterfactual uses of these words needs to give way.

Regarding faith specifically, The scientific pantheist and the utilitarian will agree that the supernatural dogmas that have been handed down to us are not worthy of faith because there isn’t enough evidence for them, and because they are now obviously parochial. However, the pantheist, deists, and theists can claim the the secular utilitarian ethos (that most atheists appear to adhere to) of well-being of conscious creatures also tends too much towards the parochial.

To be clear, faith, defined as the belief in something without proof, encompasses a whole spectrum of degrees of likelihood. For example, when I am driving my car on the highway, I don’t have definitive proof that the next oncoming car won’t suddenly swerve into my lane and kill me. But I have enough evidence that I have a fair degree of faith that it won’t happen.

However, for us conscious life forms, a profound amount of faith is still necessary. How we see reality is a mirror of how we see our lives/existence. For most of us, and for the vast majority of human history, if it isn’t/wasn’t necessary to have faith that reality is the good, then there wouldn’t be the need for all of the rituals and art that even the most secular people consume that reinforces our faith that our life(s) are worth the effort. For example, we wouldn’t go over and over to see fictitious movies, the vast majority of whom have positive endings. We wouldn’t need to. We wouldn’t regularly read novels where good triumphs. We wouldn’t listen to beautiful music and look at beautiful art that reinforces the idea and feeling that this reality is beautiful to exist in. Or at least if we did go to movies, listen to music, etc., the sum total of the art we consume would intentionally be neutral or downright ugly or bad, or at least as much ugly and bad as it is beautiful or good.

So yes, Scientific Pantheism is a religion. It not only has an ethical paradigm that establishes a hierarchy of values that descends from the reverential love of reality/nature/God (down the right side of the mandala in the first post (Link)), it also has, or would require, rituals, the demarcation of “sacred” spaces, etc. like any religion (see the left side of the same mandala), in order to cultivate the faith in, and love of, this reality that is pragmatically required/necessary if you and I, and our descendants, are to be successful in and a part of this reality. And hey, we are fortunate that thus far Einstein, the greatest scientist of our era, was also pretty much a model practitioner of scientific pantheism; so anecdotally at least we can say that some faith in a benevolent universe doesn’t necessarily lead to bad science.

So yes, Scientific Pantheism is a religion. It not only has an ethical paradigm that establishes a hierarchy of values that descends from the reverential love of reality/nature/God (down the right side of the mandala in the first post (Link)), it also has, or would require, rituals, the demarcation of “sacred” spaces, etc. like any religion (see the left side of the same mandala), in order to cultivate the faith in, and love of, this reality that is pragmatically required/necessary if you and I, and our descendants, are to be successful in and a part of this reality. And hey, we are fortunate that thus far Einstein, the greatest scientist of our era, was also pretty much a model practitioner of scientific pantheism; so anecdotally at least we can say that some faith in a benevolent universe doesn’t necessarily lead to bad science.

Faith is a necessity. For the vast, vast, preponderance of the history of reality you and I (infinitesimal motes that we are) either, didn’t yet exist, or, we will be dead. Save possibly as a link in the forward moving thermodynamic process of life, we will all be utterly forgotten. And, consider that sometimes for all of us, and quite often for many of us, this life can be ferociously hard. So, why bother? . . . Because, the scientific pantheist has seen enough, lived enough, with eyes wide open, to feel that this reality, this mysterious yet profoundly comprehensible and beautiful universe, this indifferent existence, is generally worth our love, reverence, empathy, and serious effort; intergalactic voids, worms, warts, plagues, earthquakes, supernovas, and all. To take this often extremely difficult existence on, ya gotta believe in the beauty/goodness of reality. So, for the difficult times a wise scientific pantheist, of necessity, cultivates faith.

18. What is Life?

18. What is Life?

The foundational meta-ethical prescription/argument of scientific pantheism is: Reality in general (the universe) is the good, so act in accord with reality. As one does this an ethical hierarchy forms, from what is most generally the case down the hierarchy to what it means to be an individual. And at perhaps the halfway point in that hierarchy is the prescription to act and be in accord with the best scientific definition of life. i.e. For a scientific pantheist accepting that this material reality is the good, acting in accord with the definition of life in a crucial sense also becomes the Meaning (purpose) of life.

So, getting the definition of life correct, scientifically correct, becomes a very big deal, ethically. As stated above, this is the definition:

Life is: an individuated metabolic process (thermodynamic dissipative structure) that has become organized around the ability to creatively* avoid its own dissolution (through sensing and responding to its environment).

*The concept of creativity, as it is used here, doesn’t necessarily require conscious intent. Creativity can be here defined as, any natural process (algorithm) where functional order is formed out of chaos, and at some point in that algorithm a random variable is interjected such that the new order is relatively unique. Some examples: The root ball that any tree in a forest creates is unique. The particular exact path any bee creates to get pollen and nectar out of the flowers in a meadow is unique. A new species created via natural selection is unique.

*The concept of creativity, as it is used here, doesn’t necessarily require conscious intent. Creativity can be here defined as, any natural process (algorithm) where functional order is formed out of chaos, and at some point in that algorithm a random variable is interjected such that the new order is relatively unique. Some examples: The root ball that any tree in a forest creates is unique. The particular exact path any bee creates to get pollen and nectar out of the flowers in a meadow is unique. A new species created via natural selection is unique.

And why this particular definition of life? Because this definition simply explains not just what all of life is in terms of its characteristics, but also leads us to why and how life came into being and exists (in terms of physics, which applies, beyond earth’s biosphere, to the entire universe). Thus it is the best definition because it transcends mere description to provide an accurate theory of life:

- Via the 2nd law of thermodynamics, energy dissipates.

– Matter in some configurations can be reactive as energy dissipates through it, thus dissipative structures can form.

- Over time, as energy moves through dissipative structures, those structure that are more resilient will be naturally/randomly selected for.

- The most resilient dissipative structure(s) would be organized around a creative process (see comment* in italics above) that allows the structure to change to avoid dissolution. Once this happens there is life.

In science an empirically sound theory is a profound step up from as an explanation, from a simple description of the observed data. Compare the explanatory theory above to the complex and puzzling standard mere descriptive attempts at an “explanation” of life in this lecture: (lecture), or in the “definition” below:

Wikipedia: ”The definition of life is controversial. The current definition is that organisms are open systems that maintain homeostasis, are composed of cells, have a life cycle, undergo metabolism, can grow, adapt, to their environment, respond to stimuli, reproduce and evolve.”

Unlike the Wikipedia definition, which just lays out the characteristics of earthly life, the definition in bold above ties the characteristics together by explaining them in terms of the laws of physics that gave rise to life. So, again, given an open thermodynamic system, where energy is constantly being added, and given that same system has a sufficiently complex and reactive stew of chemicals such as existed on the earth’s surface: complex dissipative structures will continuously form. And, thus (given enough energy, matter, and time) chance and simple chemical dissipative structural evolution has inevitably (on earth at least) caused a dissipative chemical structure to become organized around the ability to creatively avoid it’s own dissolution (life). And that definition also helps us understand life in some uncommon ways:

For example, the definition leads us to the unexpected conclusion that life isn’t so much characterized by change as it is by stability. Once a dissipative structure that can creatively avoid it’s own dissolution comes into being, and if the energy supply continuous (our sun), then that structure may become far more stable/resilient than other dissipation structures. For example, on the surface of this earth, fires and rivers are thermodynamic structures (which dissipate the sun’s energy) that come and go. Coal or wood fires may last weeks or even years, and rivers may last for millions of years. But the single dissipative structure that is life has been around for billions of years.

Another uncommon way to understand life thus defined: all earthly life is one; as in, it is all one dissipative three to five billion year old structure. It is merely our egoistic myopia that misguides us, as “individuals”, to think that we are truly separate life forms. We are not. We are one dissipation structure, connected, via reproduction to the original cell. Reproduction doesn’t so much make us separate (in a way that would be valid for the most functional/scientific definition), as it is simply a way (via reproduction and natural selection) that life (the dissipative structure) creatively avoids dissolution. The analogy that may help make this clear is multi celled organisms: “separate” organisms are an individuated part of the whole dissipative structure that is life, in an analogous way to cells being an individuated part of a multi-celled organism such as yourself. Individual cells may come and go (live and die), but their death is relatively irrelevant. The greater organism remains. So, likewise, organisms may come and go but the dissipative structure that is life remains. Although one may feel diminished as a mortal individual by this realization, one can also feel elevated by the realization of one’s collective identity as part of a billions of years old structure. Try contemplating that next time you are out walking in a forest. And Einstein said that is our “task” anyway, right? Life, which we are a part of, properly defined, is immortal! Well, billions of years old isn’t immortal, but from the perspective of an average human’s 80 year “lifespan” (<<Ha!) it might just as well be. . .

Another uncommon way to understand life thus defined: all earthly life is one; as in, it is all one dissipative three to five billion year old structure. It is merely our egoistic myopia that misguides us, as “individuals”, to think that we are truly separate life forms. We are not. We are one dissipation structure, connected, via reproduction to the original cell. Reproduction doesn’t so much make us separate (in a way that would be valid for the most functional/scientific definition), as it is simply a way (via reproduction and natural selection) that life (the dissipative structure) creatively avoids dissolution. The analogy that may help make this clear is multi celled organisms: “separate” organisms are an individuated part of the whole dissipative structure that is life, in an analogous way to cells being an individuated part of a multi-celled organism such as yourself. Individual cells may come and go (live and die), but their death is relatively irrelevant. The greater organism remains. So, likewise, organisms may come and go but the dissipative structure that is life remains. Although one may feel diminished as a mortal individual by this realization, one can also feel elevated by the realization of one’s collective identity as part of a billions of years old structure. Try contemplating that next time you are out walking in a forest. And Einstein said that is our “task” anyway, right? Life, which we are a part of, properly defined, is immortal! Well, billions of years old isn’t immortal, but from the perspective of an average human’s 80 year “lifespan” (<<Ha!) it might just as well be. . .

Thus, meta-ethically, if we want to be in closest accord with this reality, we as living organisms should choose to be in closest accord with the definition of life. So we should care about doing our part to keep the, thus far “immortal”, metabolic process going (or dissipation structure) as far into the future as we can influence. How? Well that is a complicated question, but normally it’s probably most economical, pragmatic, and evolution-airily psychologically satisfying to start locally with maintaining the metabolic/dissipative process in and through ones’s own body. Because, if nothing else, it’s obviously functionally easier to breath, eat, and provide clothes and shelter for yourself and your family first before you can even have the ability to do the same for the larger world. The old adage, “think globally, act locally”, still makes sense.

Finally, as an aside, the definition above helps us answer the question: When would or could A.I. or a computer viruses be alive? They could be, and considering the definition above, science fiction may help us out with knowing when the threshold might be crossed. Why would most people consider HAL or the women in Ex Machina alive? Well they are dissipative structures, and when we conclude that they are actively organized around creatively avoiding their own dissolution we empathize that there is a fellow life form, and thus we are conflicted even when they attack a human. Particularly if that human is rather bland and passive (as in 2001), or a sociopath (as in the robot’s creator in Ex Machina).

Welcome to Resolving the Debate

Welcome to Resolving the Debate

Welcome to Resolving the Debate

This blog seeks to resolve some of the most damaging disputes that plague our civilization. How? – by appealing to first principals.

The reason for the creation of this site is to illuminate basic but grand concepts about the human situation, the nature of reality, logic, Meaning, goodness, and beauty and apply them to the crucial debates of our time. Admittedly this is a difficult task, and it has been somewhat neglected in our modern political/social climate, but it is deeply necessary. Why? Because finding the foundations of a common worldview for humanity is simply the most peaceful and functional way to actually resolve destructive intractable debates. We can use these deeper common principles to direct us at the more superficial level on which most of our disputes normally take place. Check it out!

You may want to view the new introductory videos I’ve put on the Great Issues Rose Mandala and Reverence tabs above. ↑

Hopefully you will also find it exciting to see that many of the deep debate resolving ideas on this blog are fairly unique. You may even find this blog a little uncomfortable because the positions it takes will be different then those taken by current crucially important interest groups/blocks; for instance the standard secular versus religious and socialist leaning versus capitalist dichotomies are largely erased and replaced with larger world view dichotomies.

And some of the ideas here may have the power to change your life:

Concerning Socialism versus Capitalism > Imagine humanity having the intellectual tools to really move beyond the core political debate. . . . Please spend a little time and check out the provided PowerPoint’s, concepts, and charts. See how the roots of the two opposed political and economic ideologies are tied together from a ‘Natural Law’ perspective via the lens of modern science. Here

Concerning Religion ‘versus’ Science > The key to resolving many human debates is awareness of the importance of cultivating an enlightened reverence for the deep reality that we can all agree we share. more

Concerning Epistemology and Logic > What would it mean if the common reality that we all share really is ultimately just finite and relative? -As opposed to infinite, or absolute. What if the success of the scientific method suggests a finite and relative metaphysics that should have already led philosophers and scientist to anticipate something like the microcosmic world of quantum physics? What if the micro world of quantum physics defines a common sense boundary of this finite reality rather then the mystery laden puzzle within an infinite and absolute reality as quantum physics is typically portrayed? And what if understanding that idea, really understanding it, and it’s corollaries, leads to an awareness that this reality is profoundly knowable, and that most of the paradoxes that have plagued modern philosophy are unreal. What if there is a logical path, now open, to a unifying philosophical worldview that, not coincidentally, is also no more prone to dogmatism than the world view that has been created by the modern scientific method? more

Concerning Metaphysics > Consider the debate resolving unity that could occur if humanity finds a common core definition of ‘god,’ that virtually everyone would, of their own will, want to revere. Consider how this idea would be a challenge to religious ‘fundamentalists’ as much as atheists, and consider what precisely that implies about the human existential situation.. more And, examine a new perspective on the existential and social necessity of using a commonly agreed upon definition of god as a starting point for objectively defining reality. more

Concerning a central diagram for philosophy and for understanding the Meaning of Life >

“Dear humanity, please study the Rose Mandala for it is the map and the compass.” – //Tlili

Premise #1: The Rose Mandala is the most workable, and therefore best, ethical compass for humanity to create a gracefully sustainable civilization. In other words, the Rose Mandala is the key to creating a gracefully sustainable civilization.

The Rose Mandala is a diagram that will show you the fundamentals of how we lost our way and the path we may take to move forward. On some levels it is profoundly simple, on others profoundly complex. It contains the latest modern understanding of reality, and it is primordially ancient.

The Rose Mandala ties ‘it’ all together: the subjective and the objective, the sciences rationally ordered and freewheeling spirituality, God and the self, the spiritual paths we take and how the meaning of life is also the objective definition of life. It sums up proper logic, metaphysics, epistemology, easthetics, and ethics. Please study it, but if you must only learn one thing from it please observe that living in harmonig with the definiton of life comes BEFORE the pursut of happiness for not understanding that is the core reason humanity has lost its way. more

Concerning who is most responsible for the crises that our civilization is experiencing. > The Philosophers. more

Concerning the degree to which humans are in agreement about ’The Meaning of Life,’ and why > more

Concerning the importance of, and how to stimulate, Free thinking and civil discourse,

Concerning the roots of, and importance of, Reasonable environmentalism.

It’s 2012, and the time to make the world better is NOW!

Most of us agree that our civilization could really use some major positive changes. But beyond that very general and vague consensus we fall into disagreement over a specific course forward. What to do? Is it cynicism or realism to deride a new attempt to create significantly more consensus?

Throughout the history of civilization many people have felt that perhaps humanity could move forward with less conflict and more progress if most of us could agree on first, or unifying, principles. The questions that most think are crucial are old questions:

How do we, and can we, really know what reality is? Is there a single theory, a ‘unified field’ theory, of everything? Are there really just four noble truths as the Buddha said? Does God exist, and is there just one god? Is ‘God’ the Judeo-Christian God? Or is God the God of Islam? Or is our conception of God simply too parochial, or is there even a God at all? Are Christians correct when they speak of the importance of Jesus as the ‘savior?’ Is there one or a basic type of substance from which we are all made? What is the Meaning of Life and can we agree on it?

Many would say that the very definition of philosophy is that it is the human endevor that seeks to find unifying principals: those essential concepts that make the most coherent world view. Others advocate for finding unity via religion. And of course still others seek to make peace with diversity. And most concede that, unlike science, philosophy has not really ‘progressed’ as such; they say that the philosophy of someone like the modern acclaimed philosopher, Foucault, isn’t necessarily a progression over an ancient’s like Aristotle’s. The worldview philosophy that can achieved by contemplating the Rose Mandala has the advantage that it is not based on absolute deductive arguments that can be disproved, but rather the Mandala is a tool that individuals can use to integrate their versions of an ever expanding consciously induced worldview with one another. more